By Victor Henry, Research Analyst at King’s Private Equity Club

- Published as part of our ‘Deep Dive’ Section, promoting in-depth pieces which analyse underrepresented issues and challenge conventional narratives.

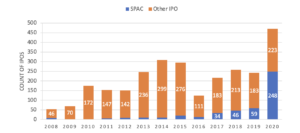

SPACs (Special Purpose Acquisition Companies) have been under the spotlight in recent years. The US SPAC market had a fantastic year in 2020 with more than $80 billion in SPAC issuance. Data shows that the popularity of this new investment vehicle worldwide is increasing: In 2015, there were 20 SPACs with roughly $3.9 billion of funds raised while recent data reveals that almost 489 SPACs went public in 2021 and raised more than $136.7 billion, according to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. The US is currently the world leading issuer, but Europe seems to be slowly following in the US footsteps.

Figure 1: SPAC issuance in the US vs Europe since 2016.

Figure 1: SPAC issuance in the US vs Europe since 2016.

Source: Refinitiv Eikon, May 2021

Despite the recent success, there are limitations to this facilitated route for companies to go public which is starting to worry investors. In Q2 2021, SPAC IPO activity has slowed down significantly as the pandemic era SPAC boom in the US has lost its momentum. Before explaining why the SPAC ship might be sinking, it is crucial to understand what these investment vehicles are.

What are SPACS?

SPACS refers to a blank check (shell) that has no commercial operations and is formed strictly to raise capital through an initial public offering (IPO) or the purpose of acquiring or merging with an existing company. The acquisition takes place through a business combination (when a privately owned company merges with a SPAC) also referred to as a de-SPAC transaction. Once created, the shell company has 24 months to engage in such a transaction. Indeed, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) grants SPACs two years from their IPO, by which they must find a suitable private company to acquire, otherwise, the company is liquidated, and investors get their money back with interest.

SPACS are initially formed by highly qualified groups of individuals such as hedge funds, private equity funds, or entrepreneurs, which invest nominal capital in exchange for founder shares. Usually, the sponsor owns a 20% interest in the SPAC post-IPO. The remaining 80% is held by public shareholders through shares offered in the IPO.

Once the capital is raised, the sponsor starts identifying the potential private companies that match the terms and conditions specified in the IPO. The valuation is negotiated between the sponsor and the target company, as in an M&A process, and, importantly, the target company may offer future projections to the sponsors in order to set a value for the business. Once the target company has been selected, the business combination approved and the merger closed, the de-SPAC process occurs, where the target company becomes a public listed entity. The SPAC transforms into a private company taking on its name. Investors who owned shares in the blank check company now own a piece of the new public entity.

The pandemic-era SPAC boom

SPAC activity has almost quadrupled in 2020 and investors claim that they represent a more efficient and rapid way for private companies to go public. Indeed, private companies have been shifting to special purpose acquisition companies to bypass the traditional IPO process and gain rapid public listing.

The Covid-19 pandemic triggered a rapid increase in the popularity of SPACs due to increased market volatility. With company valuation crashing overnight, a significant amount of IPO deals derailed at the last minute, triggering hesitance among investors in the primary market.

Because SPACs are initially formed by corporate leaders (private equity funds and hedge funds, which are known for executing profitable deals), it ensures greater certainty of execution. The experience and track record of such institutions encourage the investors to take part in deals and gives the investor an opportunity to invest in a competent management team.

Figure 2: Total number of IPOs in the US since 2008

With a SPAC deal record year during the pandemic, more blue-chip investors and large institutions are taking part in underwriting SPAC IPOs and many of the companies going public through such IPOs are experiencing big valuation. An example is Goldman Sachs’s first SPAC deal with Vertiv Holdings valued at a $5bn. The share prices have more than doubled since.

The success of SPAC deals, such as Vertiv Holdings, is also due to efficient marketing. Once the acquisition target company is identified, the vehicle can start promoting the acquisition to investors before the stock starts trading. The public communication of the transaction raises investor interest in the shell company and consequently raises its share price. Once the deal is closed and the de-SPAC transaction takes place, the public communications team advertises the success of the deal which gives the share price another push. Through this mechanism, SPAC sponsors benefit from rising share prices and have an incentive to publicly communicate the development of their deals through public relations activities. However, this artificial share price increase has some limitations.

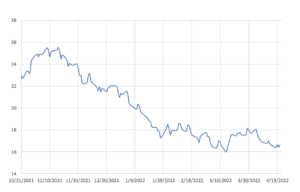

Figure 3: The defiance next-gen SPAC ETF (SPAK US Equity) from November 2021 to April 2022. Source: Bloomberg

Recent SPAC IPOs have been struggling to find their place in the market. The defiance next-gen SPAC ETF, which tracks the performance of recent US-listed common stocks of SPACs, shows a total return of -35% since November 2021.

On top of that, SPAC deals have experienced a rush of cancelation in 2021. In total, some 17 SPAC mergers, valued at a combined $37.2 billion, have been dismissed during the last six months of 2021, compared to 4 deals worth $720 million during the six months prior.

US SPACs are declining, but why?

According to a Bloomberg Law article, 14 out of 24 of the companies that went public as a result of a merger with a SPAC from 1 January 2019 until 10 February 2021, “reported a depreciation in value as of one month following the completion of the merger”. This poor after-market performance is due to “absurd” financial projections of target companies according to Nate Koppikar, co-founder of hedge fund Orso Partners. As a result, SPACs are often purchasing overvalued companies and underperform once traded on an exchange. Michael Ohlrogge and Emily Ruan added in a paper that the dilution of shares from the fundraising activity misleads the true value of companies’ stock.

Some SPACs struggle to achieve their fundraising targets to meet the requirement of their deals. The reason is that institutional funding is harder to attract, and public investors are brutally dumping stocks. The 2-year deadline for shell companies sometimes leads to sub-optimal deals as SPACs are pressured to return the funds raised to investors. As the company is brought public, it struggles to meet the financial objectives set by the sponsor, and shareholders start to sell the stock. The digital health company UpHealth Inc is a good illustration of this mechanism. The firm’s share price has dropped by almost 90% in less than a year since it went public through a SPAC in June 2021 (Bloomberg data above).

Another key challenge arising in SPAC deals is the management continuity post IPO. In a traditional public offering, the company’s management has direct interactions with their future shareholder to agree on the composition of the management team. In a de-SPAC transaction, the terms are discussed between the sponsor and the target company and in some cases result in changes to the management team of the target company. Once the transaction closes, the sponsor has decision-making power at the expense of historical shareholders who will lose some control. Without the experience of historical owners, the new management team can struggle to understand the target sector leading to a rough transition.

Finally, the popularity of SPACs has been greatly deteriorated by fraud allegations. Because SPAC IPOs are much quicker, investors sometimes lack time to scrutinize the company for fraud and conduct appropriate due diligence. It is the case of Nikola, a start-up willing to develop electric and hydrogen trucks. The company made numerous false assertions regarding the vehicle’s technology and working prototypes. The company shares had jumped following a SPAC IPO, but the stock price fell by more than half following the scandal. Similarly, other companies have been releasing misleading statements and lying about profitability to bolster their valuation.

To resolve these issues, the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) recently proposed new policies demanding target companies to follow more stringent disclosure procedures relating to future projections, conflict of interest, and potential dilution upon issuance of additional shares. However, experts doubt these new measures will fix the problem.

Conclusion

The enthusiasm for SPACs seems to progressively slow down and yield towards an equilibrium. Returns after mergers have been below the market, deal cancellations have risen alongside vehicle liquidation, and target companies are considered to be massively overvalued. While critics say that the blank check boom is not here to last, special purpose acquisition companies still serve a purpose, especially during times of high market volatility. They offer advantages over time-consuming traditional IPOs by providing businesses with capital from investors and managerial expertise from sponsor teams. On the other hand, SPACs offer a great exit opportunity for both venture capital and private equity firms willing to liquidate their assets.

Despite a record year of SPAC issuance and capital raised, the future of SPACs is rather uncertain. Speculations on a potential market recovery fail to convince investors who see deals struggling to make it to fruition.