By Lautaro Clavero, Student at the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba

As Steven Landsburg stated in more than a clear fashion in his famous book “The Armchair Economist,” the economic science can be summarized in 4 words: “People respond to incentives”. As clear as the quote may be, it implies powerful consequences, namely, any policy that isn´t aligned with the expected “rational” economic behaviour, can create extremely counterproductive results.

For example, in 1946, San Francisco faced a housing problem after the Second World War due to the expansion of the city´s population by a third in the previous six years. This problem resembles (in nature, not in causes) the 1906 one when an earthquake followed by a fire in the inner city destroyed the homes of over 225.000 people. In 1946, the authorities saw the increase in demand as a future increase in the cost of living.

In order to alleviate the problem, they tried to reduce the cost of rent by law, imposing a maximum price in housing and apartment rent, in contrast to the market solution based on free prices in 1906. The “maximum prices policy” results were a disappointment at best. For every 375 rental demands, there were only 10 rental offers, whereas in 1906, for every 1 rental demand, there were 10 rental offers after the earthquake.

It goes without saying that applying a single study case to the general is a logical fallacy. However, the previous example draws a basic yet important premise in the economy that is often ignored: People act according to their best interest, meaning they are constantly trying to maximize their utility, restricted by their context.

On this same line, Argentina is an exceptional case study. In the last century, it became a laboratory for bad economic policy making, equally ignoring textbooks and common sense. Leaders often disregard long-term stable growth and prosperity and frequently lean towards short-term patches to amend previous inexpedient decisions. Many of those decisions ignored the incentive structure that was being created underneath. Therefore, the results obtained were rarely expected. Probably the best example of this is the social assistance programs that became relevant in the early 2000s.

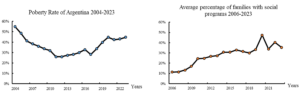

At the start of the millennium, Argentina faced the worst crisis in its history. Poverty reached its highest level at 67%, along with extreme unemployment of 21.5%. This chaotic scenario developed with a political catastrophe that ended with the resignation of Fernando de la Rúa, the president until then. Two years later, when the economy started to recover, Nestor Kirchner was elected for office…

With some “old-fashioned heterodox ideas” and political purposes, he vastly expanded government expenditure. Most of the spending was allocated to social programs that are still in high demand due to the economic situation. Some economists argue this welfare policy, matched with other items of the expansive fiscal plan, such as the transport and energy subsidy, was responsible for the high-speed recovery. Still, the economy was already experiencing a rebound effect from the crisis. It´s worth mentioning that the administration mainly financed the increase in expenditure with more taxes and seigniorage (printing money). Therefore, one could argue consumption is raised at the expense of investment.

Source: Own elaboration based on data from the Central Bank of Argentina, World Bank, and International Financial Statistics (database).

Nonetheless, assistance was indeed required at the time; however, it was never replaced with a long-term solution. There was no plan to transform those social programs into productive work. Moreover, the number of government payments kept increasing even though poverty was rapidly declining, and, in fact, families managed to collect almost as much government assistance as the average working household income.

Source: Own elaboration based on data from the Central Bank of Argentina, World Bank, and International Financial Statistics (database).

As a result of this welfare policy, paired with a rise in labor taxes, more powerful unions, and strict work laws, the opportunity and financial cost of work grew. People didn´t have the incentives to work if they could get cero production hours for a similar amount of money as with a job.

Companies, on the other hand, had to pay alongside the salary 50% of its equivalent to the government, parallel to a bigger risk of taking new employees. Hence, no new formal jobs have been created since 2007, causing real wages and productivity to collapse.

In the end, the incentive structure completely shifted. The private sector of the economy lost its profitability to maintain a subsidizing government that rewarded work-shyness and punished effort and investment. What seemed like social-friendly policies evolved into an economic disaster that hit the hardest on those it claimed to help.

Lautaro Clavero

Lautaro is a non-official ambassador of the Patagonia region where he was born. He is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in economics atUniversidad Nacional de Córdoba. During 2021, he conducted his radio program “La economía en una lección” (The economy in one lesson), while, at the same time he started to write as a journalist. His main interest includes Macroeconomics and statistics, being a teaching assistant for those same subjects at his university.