By Agrin Ayhan, Student at King’s College London

Iran discovered what might be the second-largest lithium deposit in the world. What does this mean for lithium prices?

The 8.5 million tons discovered in the country’s mountainous province of Hamedan is equivalent to 10% of the world’s lithium supply. The rare element is a crucial component in the cathodes of lithium-ion batteries in EVs and rechargeable batteries like the ones in cell phones. This news, if true, would be the lifeline for the country’s economy.

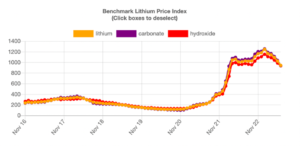

Lithium prices have sky-rocketed with the rising demand for EVs and achieving net zero.

Source: Benchmark Mineral Intelligence

Analysts at Goldman Sachs see lithium dropping in price.

“Over the next 9-12 months, we are progressively more constructive on base metals, whilst expecting a move lower in lithium prices alongside cobalt and nickel,” a report from the bank’s commodities research desk from late February wrote.

In the next two years, Goldman expects lithium’s supply to grow on average by a substantial 34% year on year, led by Australia and China, which hold some of the world’s largest metal supplies.

“Hence, whilst a recovery in EV sales into 23Q2-Q3 could temporarily lift sentiment and support falling battery metal prices, the likely supply surge and downstream overcapacity are set to bring lithium prices down subsequently in the medium term,” the bank wrote.

Depending on Iran’s capacity to export, such an addition to the world’s known lithium reserves may also push the metal prices down. Also, very little is known about the new deposit regarding the grade and quality of the metal.

Why this discovery may not affect lithium prices/cause prices to fall:

- No infrastructure or FDIs: “Energy and infrastructure costs are particularly high, and there are no foreign direct investments (FDIs) to support the Iranian mining sector,” according to Raphaël Danino-Perraud, a research fellow at the French Institute for International Relations (FIIR).

- “We can easily do without Iranian lithium,” according to Marc-Antoine Eyl-Mezzega (FIIR). No Western companies will want to invest in Iran. Only the Russians and the Chinese could look into it”. It does not seem like any mining activity will affect prices in the short-medium term. Danino-Perraud further explains that energy investments in Iran, should they get started again – and they won’t in the near future, he added – would most likely focus on gas, not lithium.

- EU Critical Raw Materials Act: requires 10% of EUs consumption of strategic raw materials should be mined in the EU. The European Commission is seeking to introduce targets of 10%-40% of the mining, recycling, and processing of critical raw materials used in the bloc to be done in the EU by 2030. In other words, they do not look interested in buying Iranian lithium.

However, I believe that prices will continue to rise.

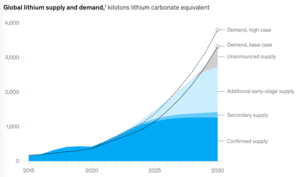

- Demand outpacing supply

According to the US Geological Survey, in 2022, batteries denominated the global end-use markets, absorbing 74% of the global lithium production. This figure is only said to rise.

Source: McKinsey & Company

With China, the USA, and the EU planning to decarbonise their economy, Fitch Solutions estimate that EV sales are expected to almost triple from 2021 to 2026. China alone, which accounted for about half of EV global sales in 2021, is expected to triple its EV sales by 2026.

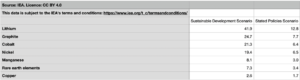

Mineral demand for use in EVs and battery storage is a major force, growing at least thirty times by 2040. Lithium sees the fastest growth, with demand growing by over 40 times in the Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS) by 2040, followed by graphite and cobalt.

Source: Iea

The largest source of demand variance comes from uncertainty around the stringency of climate policies. The big question for suppliers is whether the world is heading for a scenario consistent with the Paris Agreement.

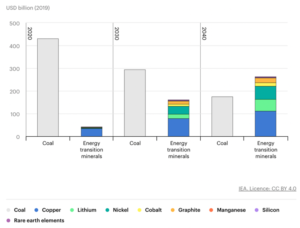

Coal is currently the largest source of revenue for mining companies by a wide margin. Today’s revenues from coal production are ten times larger than those from energy transition minerals. Accelerating clean energy transitions is set to change this picture. There is a rapid reversal of fortunes in a climate-driven scenario, as the combined revenues from energy transition minerals overtake those from coal well before 2040.

Source: Iea

The prospect of a rapid rise in demand for critical minerals poses huge questions about the availability and reliability of supply.

In the past, strains on the supply-demand balance for different minerals have prompted additional investment and measures to moderate or substitute demand. Still, these responses have come with time lags and have been accompanied by considerable price volatility.

Some minerals, such as lithium raw material, are expected to be in surplus soon, while lithium chemicals might face tight supply in the years ahead. However, after the medium term, projected demand will surpass the expected supply from existing mines, and projects under construction are estimated to meet only half of the projected lithium requirements by 2030.

- Environmental concerns

The concentrated effort to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement would mean a quadrupling of mineral requirements for clean energy technologies by 2040. To hit net-zero globally would require six times more mineral inputs in 2040 than today.

The environmental issues surrounding the production and processing of mineral resources can harm local communities and disrupt supply. Consumers and investors are increasingly calling for companies to source sustainably and responsibly produced minerals. Without efforts to improve environmental and social performance, it may be challenging for consumers to exclude poor-performing minerals as there may not be enough high-performing minerals to meet demand.

- Declining resource quality

In recent years ore quality has continued to fall across a range of commodities. For example, Chile’s average copper ore grade declined by 30% over the past 15 years. Extracting metal content from lower-grade ores requires more energy, exerting upward pressure on production costs, greenhouse gas emissions, and waste volumes. Lower-grade ores also generate larger amounts of rock waste and tailings that require careful treatment.

- Supply-side vulnerabilities

The production and processing operations for many energy transition minerals are highly concentrated in a small number of countries, making the system vulnerable to political instability, geopolitical risks, and possible export restrictions. The world’s top three producing nations control over three-quarters of global output for lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements. In some cases, a single country is responsible for around half of the worldwide production. The concentration level is even higher for processing operations, where China has a strong presence across the board. China’s share of refining is around 35% for nickel, 50-70% for lithium and cobalt, and nearly 90% for rare earth elements.

Mining assets are exposed to growing climate risks. Given their high-water requirements, copper and lithium are particularly vulnerable to water stress. Over 50% of today’s lithium and copper production is concentrated in areas with high water stress levels. Bolivia’s San Cristóbal mine reportedly uses 50,000 litres of water daily, and Chile’s lithium mining companies have been accused of depleting vital water supplies. Several major producing regions, such as Australia, China, and Africa, are also subject to extreme heat or flooding, which poses greater challenges in ensuring reliable and sustainable supplies. High levels of concentration, compounded by complex supply chains, increase the risks that could arise from physical disruption, trade restrictions, or other developments in major producing countries.

Agrin Ayhan

Agrin is a second-year mathematics undergraduate student at King’s College London, graduating in 2024. Along with being on the university fencing and swimming team, Agrin enjoys researching commodities and natural resources. In his spare time, Agrin likes collecting Soviet-era classical vinyls and perfecting his method of pouring a pint of Guinness.

I’ve been surfing on-line more than 3 hours nowadays, but I never discovered any attention-grabbing article like yours. It¦s beautiful price sufficient for me. In my opinion, if all webmasters and bloggers made just right content as you did, the net will probably be much more useful than ever before.