By Jingyi (Jennifer) Wang, Outreach Officer at the KCL Commercial Law Society

- Published as part of our ‘Deep Dive’ Section, promoting in-depth pieces which analyse underrepresented issues and challenge conventional narratives.

A company’s directors influence a substantial number of its decisions, pulling the company’s strings left, right and centre. However, directors must comply with section 172 of the Companies Act 2006 in exercising their decision-making.

This article aims to illuminate the weak spots in section 172 by highlighting two points of contention. First, it determines if the enforcement of section 172 is mere lip service. Second, it scrutinises if the ‘other matters’ in section 172(1)(a-f) fit the realities of modern labour markets.

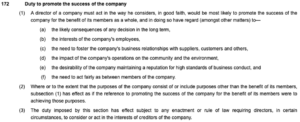

Companies Act 2006, section 172

The first step is to set out the law. The legislative control allotted to these directors is found in section 172 of the Companies Act 2006. Section 172 states that a director ‘must act in good faith to promote the company for the benefit of its members as a whole and have regard to…other matters’.

Source: legislation.gov.uk

Section 172(1)(a-f) lists these ‘other matters’ meaning the interests of all relevant stakeholders. For example, the company should have regard to employees, communities, and the environment.

Is Section 172 just lip service?

As noted, companies should regard the interests of employees, communities, and the environment, at least in an ideal world. Such encapsulates the Enlightened Shareholder Value (ESV), which calls on directors to “consider stakeholder interests in the pursuit of long-term shareholder value maximisation”.

Many legal practitioners view section 172 as a toothless tiger in its enforcement. The ‘good faith’ aspect, in section 172, is judged subjectively, making it easy for directors to comply. Furthermore, there may be good business reasons for a court to interpret ‘good faith’ broadly, thus allowing directors to slip through the cracks. Furthermore, there is weak guidance regarding the ‘other matters’ portion of section 172, which makes courts ill-equipped to handle them.

The criticisms concerning section 172 are indeed manifesting in our current markets. Statistics provide that companies’ profits grew 49% whilst US median wages only increased 1.6%. They are proving that directors pay little effort to the ‘interests of the company’s employees’ as per section 172(1)(b). “It’s obvious that corporations are trying to pass on any form of short-term pain they might be feeling…and that’s serving the top, wealthiest class instead of those in need of fair wages or products that are affordable,” said Krista Brown, a policy analyst with the American Economic Liberties Project.

Source: The Guardian

Source: The Guardian

Does Section 172 reflect the realities of modern labour markets?

Section 172(1)(b) states that directors are to have regard to ‘the interests of the company employees’, but does the term ‘employee’ exclude others such as contractors, freelancers, seasonal workers or those on other informal contracts?

Janet Williamson, senior policy officer at the Trades Union Congress, contends that this subsection is “not intended to differentiate between different parts of a company’s workforce”.

The reality is that there is an increasing number of non-employees, who should have at least some legislative protections. Self-employed individuals rose by a third since 2006. Zero-hour contracts, outsourcing and labour intermediaries are more commonplace in certain sectors.

But to what extent are employees’ interests considered by these large corporations? From a labour law perspective, classifying one as employee is significant since employees have rights and protection that non-employees do not. There is undoubtedly an issue of large companies “which have sought to maintain the control associated with “employee” status while avoiding its attendant costs”. In other words, these companies want to control their employees while denying them their status to avoid adhering to certain rights.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Uber BV v Aslam held that Uber drivers are workers rather than independent contractors. Workers hold “an intermediate status in between employees and self-employed individual[s] under English law, and therefore are afforded some rights that employees receive”. On the other hand, courts in IWGB v CAC rejected the claim that Deliveroo drivers are workers, distinguishing Uber BV v Aslam. As a result, Deliveroo drivers were “not within the scope of the right to join trade unions”.

Section 172 is aspirational, but its Achilles heel lies with its enforcement. Statistics show a disparity between the companies’ profits and workers’ wages. Even though it demands regard for employee interests, there is a trend displaying large corporations putting profits before employee rights.