By Jorge Comesaña García, BSc in Political Economy at Kings College London

By Jorge Comesaña García, BSc in Political Economy at Kings College London

Venezuela has been the centre of media attention due to its terrible economic performance over the last few years. The fact that it is one of the most resource-rich countries in the world, raises the question if it is yet again another example of the ‘resource curse’.

One of the main reasons behind Venezuela’s economic performance in the last two decades is the government’s use of institutions. This interval coincides with the time in which the ‘Chavista’ movement has been in power.

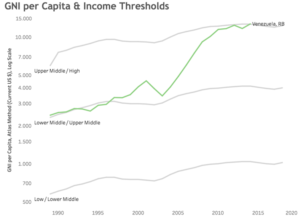

FIGURE 1: INCOME IN VENEZUELA (1990-2014)

(The World Bank, 2021)

The World Bank classifies countries’ income using the Gross National Income per capita indicator. It divides them into four categories: low income, middle income (divided in lower/upper-middle) and high income. Figure 1 shows how Venezuela was ranked as an upper-middle country, just about to reach the high-income category. The lack of transparency in recent years makes economic indicators harder to estimate. For this motive the graph only illustrated Venezuela’s progression until 2014. However, other measures (such as GDP per capita) are available. These show a massive decrease in the wealth of the Venezuelans over the last decade which has changed from around $12,000 in 2011 to around $2,000 in 2019.

Countries and their current institutions are on many occasions, conditioned by the previous ones. Often, early institutions persist and have set a base for the current ones (p.1373). In the case of Venezuela, just as in most Latin American countries, it was a Spanish colony. In the early stages, the Spanish set extractive institutions that exploited the resources and the indigenous people. Over time, these institutions evolved to become part of a more complex system (p.1183). At the time of early colonisation, Venezuela’s natural resource potential was still unknown. For this motive, institutions were established gradually and were mostly founded in the 18th century, long after the Spanish had arrived. After independence, the Venezuelan’s inherited the paternalistic view of the government which characterised the previous structures (p.117 & 124). Once the resources were found and started being exported, the administrations created to manage the latter might have adopted the same character.

Hugo Chavez’s election in 1999 was facilitated by very poor economic performance increases in poverty and the intervention of the IMF (an institution represented in the country as the expression of savage capitalism) (p. 525). The ‘Chavismo’ movement has been governing the country for more than two decades now. Chavez’s use of Venezuelan institutions led to economic growth but only while oil prices increased too. The movement used oil as a method to assure its continuity in the government. This was done at the expense of harming institutions and the future economy. As illustrated in Figure 2, prices in oil radically increased during the early 2000s. Figure 3, oil rents as a percentage of GDP, reveals the relevance of oil rents in the Venezuelan economy. His party allocated the states’ resources where they pleased and used them to eliminate political competition. Prior to this very considerable increase in prices, Chavez took over many institutions (private and public) and restructured others like the PDVSA (The Venezuelan Oil Company). Furthermore, he eliminated a series of checks and balances. His institutional reforms allowed him to have control over the country’s main source of wealth. Increases in prices provided him with the tools to extend his use of oil rents as a political tool. The latter would have been impossible without prior institutional restructuring.

FIGURE 2 OIL PRICES (1998-2021)

(Trading Economics, 2021)

FIGURE 3 OIL RENTS AS % GDP (1998-2021)

(The World Bank, 2021)

If we compare figures 2 and 3 with figure 4, we can observe how the price of oil and oil rents has influenced highly the course of the Venezuelan economy. However, given its dependency on the sector, it is odd how the regime has let it deteriorate. This deterioration, drops in prices and international sanctions have impacted the economy hugely. As a result, Venezuelans have seen a massive decrease in GDP per capita. This period coincides with the arrival of Hugo Chavez’s successor Nicolás Maduro in 2013. A period where the government has been deprived of its main political tool (oil) but where its control and misuse of institutions has increased.

Maduro has used the Central Bank to “print more money” in order to pay the debt and maintain heavy state intervention in the economy. These policies have led to hyperinflation. However, the main problem is the duration of the hyperinflation period which began around 2016 and is still happening now. Among his measures, are price-controls which in many cases, can lead to an increase in the informal economy. After his allies’ victory in the 2020 arguably democratic National Assembly elections (where turnout was only around 30%), he now has controls over all the political institutions in Venezuela.

FIGURE 4: GDP PER CAPITA IN VENEZUELA (1985-2021) *=Estimation

(Statista, 2021)

Chavismo kept or created advantageous institutions for the regime while eliminating those that were not of their interest. Their policies created an environment where trust and confidence, key factors to achieve economic prosperity, vanished. Leading to, for instance, drops in FDI over the last few years. The economic conditions are such that the World Bank ranks it as the 188th to do business in (there are 190 countries in the ranking).

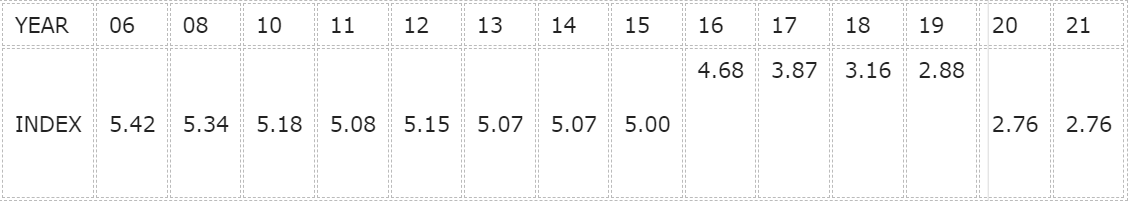

Strong democracies tend to have inclusive institutions, private property and contract enforcement are basic in systems of these characteristics. Figure 5 shows the evolution of the Democracy Index made by The Economist. The table illustrates the evolution of the Venezuelan Democracy, it shows how since 2006 (when the index began) the country has been suffering an erosion process in its democracy and therefore, the inclusivity of its institutions. Since Maduro’s arrival, the quality of institutions and democracy has decreased incredibly. As a result, in 2017 Venezuela stopped being considered a hybrid regime and started to be considered an authoritarian regime. Although the movement constantly refers to the Venezuelan Independence it seems like its institutions are more similar to the Spanish in terms of their ability to extract resources. Moreover, they share the paternalistic view of the government which tries to intervene in every aspect of the economy.

FIGURE 5: EVOLUTION OF DEMOCRACY IN VENEZUELA (2006-2021)

(Source, The Economist)

Venezuela saw a considerable period of growth during the first decade of the 21st century. This growth was mainly triggered by increases in oil prices. Chavez’s took over before the rise in prices allowed him to assure his continuity in the government. However, the extractive and paternalistic character of the institutions could only create growth while oil prices did too. Maduro’s rise to power saw an even greater deterioration of the institutions. His misuse of institutional structures and the lack of support of massive oil rents, together with other factors, created an environment where economic prosperity has been made impossible.(The Economist, 2021)

Exclusive Offer: Get £100 off your Summer Internship Experience at Amplify Trading by clicking here or using our unique discount code at the checkout: MSAmplifySummer2021. Participants graduate from the course with a Diploma from the London Institute of Banking & Finance. For more information about the course, click here.

Contributor to The London Financial

We combine research produced by students and early professionals into a single website, breaking down the barriers to entry individuals face in a number of industries.

Contributor opinions are their own and do not necessarily reflect the stance of the LF.