By Paola Martos, BSc Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE) student at King’s College London.

Economic inequality has become an important topic within the realm of politics and economics. Regrettably, such inequality is often misunderstood as a negative effect of capitalism. Consequently, governments improve their welfare state to redistribute wealth by applying progressive taxes and increasing transfers to lower income households. In Latin America, governments have made significant efforts to reduce income inequality, primarily by decreasing poverty. Unfortunately, income and wealth inequality remain high.

Peru and Chile share many comparable characteristics. As liberal market economies, they experience high levels of growth due to their economic openness. Even though their main exports depend on natural resources, these rentier states have not suffered economically from the resource curse, though it might have encouraged corruption and internal conflict. Regarding their differing results in wealth inequality, it is demonstrable that Peru’s flawed institutional framework is the reason behind its higher wealth inequality, while Chile’s Neo-liberal approaches are more satisfactory at fostering wealth creation.

Hernando de Soto, a property rights advocate, asserts that a universal formal property system for representing assets is necessary to provide an equal opportunity to poor people to convert their ‘dead’ capital into live capital. The lack of a formal system is the reason why wealth creation in developing countries has been almost impossible. Such a legal institution is essential for realising capital and creating wealth, thereby building the foundation for economic development. Moreover, financial obstacles blocking the ability to acquire assets prevents the reduction of inequality. Hence, having an institutional framework without legal discrimination is necessary to reduce wealth inequality.

Wealth Inequality

Wealth inequality illustrates a contrasting big picture and it is a component that it is challenging to analyse. Wealth matters because it aids individuals to smooth consumption when income stops flowing. To use the Gini coefficient is very misleading when comparing the economic state of a country. The Gini coefficient does not demonstrate that wealth is essentially infinite, as it can always be created. A more effective measure of wealth inequality is the ratio between the mean and median net wealth per adult: the higher the ratio, the higher the inequality.

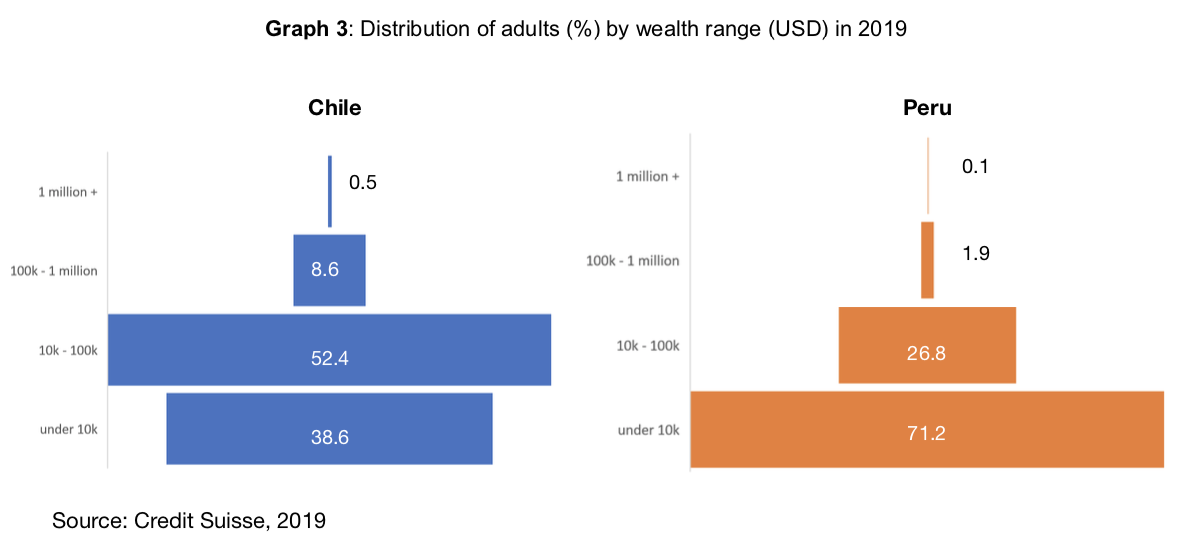

Graph 1 shows that Chilean adults have been better wealth creators than Peruvians. Graph 2 shows the real picture: Peru has experienced higher wealth inequality than Chile since the 2010 financial crisis aftermath. A wealth shock reflects the ability of the population to smooth their consumption. In other words, it shows who has enough wealth to combat the shock, and who will lose wealth due to reliance on equity. Wealth is essential, especially during an economic crisis. Peru suffered more than Chile, as most of the population did not have enough wealth to combat the shock leading to the present wealth structure shown in Graph 3.

Graph 3 shows the distribution of the adult population by wealth in Chile and Peru today. As a more developed country, half of the Chilean adult population have between $10k – $100k of wealth, which represents the Chilean middle class. On the contrary, 71.2% of Peruvian adults have wealth under $10k, demonstrating that a Peruvian middle class is almost nonexistent and a large lower class takes its place. A middle class is vital for the political economy of a developing country. Targeting policies to benefit the middle class creates a class that supports institutional changes aimed at distribution and acquisition of wealth that will benefit the poor.

The type of assets Chileans and Peruvians own is another distinction: the average Chilean’s wealth is made of more financial than non-financial wealth, while Peruvians have more non-financial wealth. Having more financial assets is advantageous, as stocks, cash or bonds are easier to liquidate than non- financial assets. Investing in these assets creates more wealth than leaving money to devalue in a savings account. The asset of most Peruvians is their houses, which is a non-financial asset, and therefore a liability as it takes more money out of their pockets in terms of mortgages, taxes, and other payments, such as maintenance.

Institutional Framework

The institutional framework of a country is an important factor to consider when trying to understand why a country has more or less wealth inequality than another. Due to disadvantaging legal and political institutions, a large sector or populations in developing countries are not able to acquire wealth. Several institutional obstacles and limitations make more impoverished populations not able to realise capital, even when they possess assets. Capital ownership guarantees a future surplus value which is essential for wealth creation. Property rights and the property system must therefore be universally enforced to provide equal opportunities to acquire property and thus wealth.

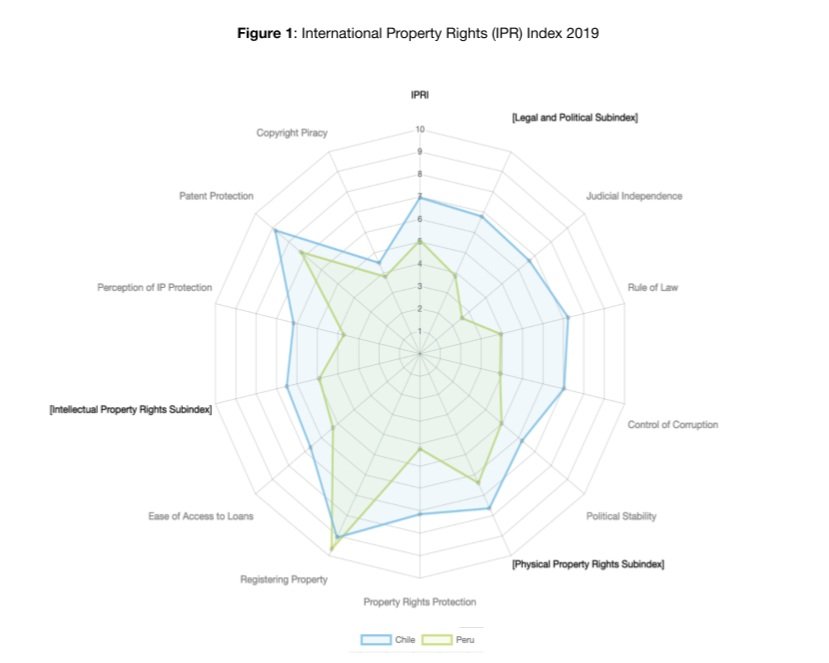

Property rights, as a formal institution, are essential for incentivising entrepreneurs to seize value for their economic activity. The lack of formal property rights hinders willingness to invest in productive assets. As we can see from Figure 1, Chile has outsmarted Peru in almost every variable related to property rights. Chile’s relative success has been mainly due to their efforts to spread ownership through the privatisation of state-owned enterprises, such as the central bank, social security and electricity, and poverty alleviation policies since the 1970s. Chile has become conscious that ownership diversification through popular, labour, institutional and traditional capitalism makes capital thrive. Their Neo-liberal policies have integrated more people into the legality of property exchange and transformed ‘the private sector into the engine of development’ and its protection enforced. Contrarily, Peru has been hindered by a long history of private land expropriation since the 1970s Agrarian Reforms. Property reforms have evolved since the 1990s, experiencing both positive results and strong opposition; for example, legally registering property is now more manageable in Peru. It might be the case that the legal requirements to approve property are minimal to reduce the cost of construction for more disadvantaged populations.

Peruvian and Chilean politics could be described as ‘organised interest politics’ since the ruling elites can influence institutions. Peruvian legal institutions have developed to accommodate the demands of Lima’s interest groups while ignoring the poor populations in the highlands and the jungle. This demographic factor is an issue that problematises the allocation of credit for small businesses. Peru exemplifies how high wealth inequality is associated with lower equality of opportunity. Chile, due to their early institutional efforts, is better equipped at providing equal opportunities to a larger portion of their population, as we have seen in the resulting distribution of Graph 3.

In Chile, corruption is punished, while in Peru, the legal institutions lack action. Figure 1 shows that Peruvian political and legal institutions are run poorly compared to Chile. A vicious circle is generated since low judicial independence is undoubtedly related to the captured democracy and makes it difficult to control corruption. Moreover, a strong, captured democracy strengthens the impact of inheritance on wealth inequality by the increased inequality of returns on capital and opportunities.

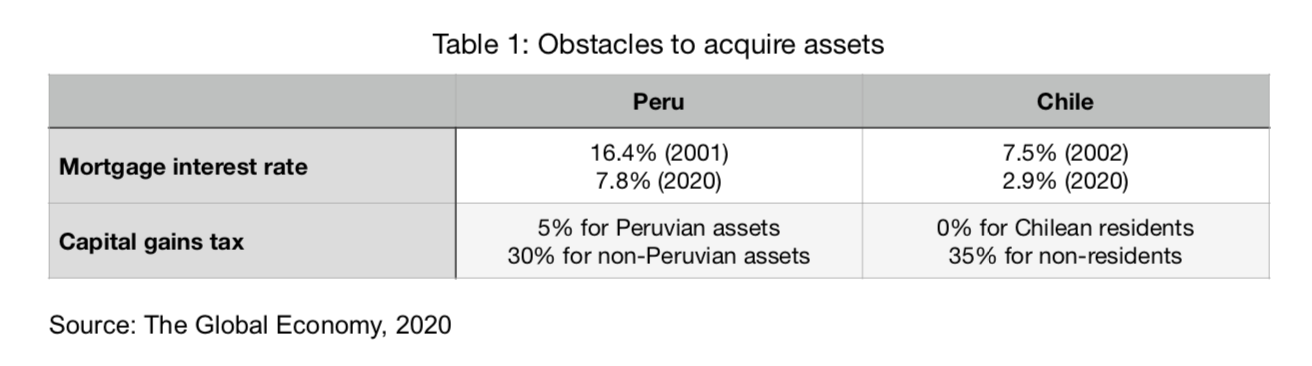

Mortgage interest rates and capital gains tax impede asset acquisition. Chile’s interest rates are affordable compared to Peru’s. A high mortgage interest rate makes it expensive for Peruvians to own real estate. Chileans are more incentivised to acquire or invest in real estate. This low tax is essential for an emerging middle-class in Chile who are the stimulators of the real estate industry. Capital gains tax is imposed on income derived from selling an asset. No taxes applied on capital gains reflects the ease for Chileans to take investment risks, while the ownership of non-Peruvian assets is restrained at the income tax level.

Astonishingly, starting a business in Chile is six times cheaper than in Peru due to bureaucratic procedures. This embodies how bureaucratic institutions hinder asset acquisition and economic development. Most importantly, during periods of high immigration, these institutions cannot merge migrants into formality. This is particularly evident in the case of the thousands of Venezuelan doctors and nurses immigrating to Peru who have to wait two years to get a license, forcing them to be extralegally underemployed despite Peru suffering from a shortage of healthcare workers. Regrettably, Peru’s high informality accounts for 73% of the workforce, which explains their ineffective progressive taxes.

In comparison, Chile’s informality is only 28,8% which shows that most of the population contribute to the welfare state by paying taxes. Nevertheless, their ‘paternalistic’ state affects perceived inequality, as the population becomes dependent on the state and decreases their entrepreneurial spirit while increasing redistribution support. Needs and resources ultimately become interchangeable. This creates economic problems given that needs are infinite, and resources are scarce.

Peru’s policy transfer from the West has been ineffective without a proper institutional framework. Emulating policies targeting inequality fail due to the lack of an impartial institutional foundation for fixating capital. Chile’s policy transfer of the Neoliberal Model from the US has worked to an extent: it has nurtured economic growth, development, and democratisation, but Chilean capitalism has consistently concentrated economic power in elites and has not been aware of the consequences.

The different institutional frameworks that Chile and Peru have, greatly affect their wealth inequality. Peru’s inability to design inclusive financial, legal, and political institutions has created adverse effects on wealth. By creating obstacles to asset acquisition and realisation of capital, they have transformed themselves into the barrier of an effective welfare state. Conversely, Chile’s neoliberal strategies are more effective at tackling issues surrounding inequality, especially that of opportunity. Peru could adopt Chilean strategies to improve its issue on property rights. Still, both countries must increase their institutional independence and stop relying on their elites for economic development.

This article was submitted to The London Financial as part of our thematic collaboration with El Cortao’ and has, accordingly, been published on both platforms. To visit this article on our collaborative partner’s website, please click here.