By Advait Lath

Global fossil fuel prices have been on a precipitous rise since the war in Ukraine began. Energy prices play a significant role in expenditures made by households, costs for producers and overall headline inflation. Inflation concerns have been recognised of late by policymakers globally, which has led to rate hikes by several leading central banks. Bears and bulls have been tussling on the financial front on an epic scale. With widespread upheavals and uncertainties permeating the lives of citizens, it may be a futile exercise to be able to pinpoint the origins of an impending global crisis. Chances are, a clandestine Russian gas behemoth, Gazprom, may have something to do with it.

Russia’s Leviathan Role in the Energy Economy

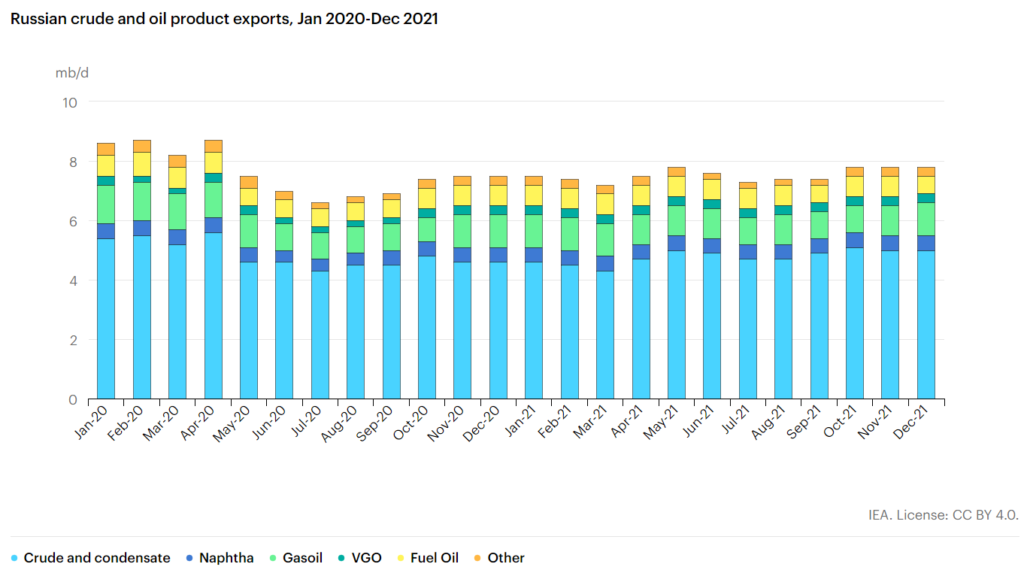

Russia is the leader in global fossil fuel extraction, refining and production. The vast transcontinental landmass that makes up the country is endowed with surfeit natural resources. It is no surprise that it is one of the world’s top three crude producers, along with Saudi Arabia and the USA. According to the IEA, 45% of Russian federal revenues were based on oil and gas in 2021. While supplying 14% of global oil output (11.3 million BPD as of January 2022), Russia heavily exports a large proportion of its total oil produce (7.8 Million BPD) predominantly to China (20%) and Europe (60%). In comparison, US’ total oil production was 17.6 Million BPD and Saudi Arabia’s 12 Million BPD. Through its extensive crude pipeline capacity, exemplified by the protracted, 5,500 Kilometre long Druzhba pipeline network, Russia transports 0.75 Million BPD of crude to Eastern and Central European refineries. Following an Asia-centric energy policy pivot, Russia launched a 4,740 Kilometres, 1.6 Million BPD pipeline to China and Japan in 2012, as a measure to reduce dependency on European exports.

Fig 1: Russian Oil exports and their composition. (Source: International Energy Agency)

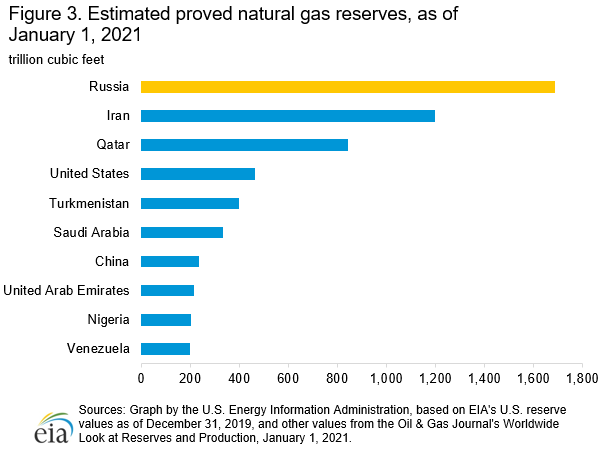

Behind only the US in terms of natural gas production, Russia is home to the world’s largest gas reserves and is the largest exporter of natural gas in the world (See Fig. 2). In 2021 the country produced 762 bcm of natural gas and exported approximately 210 bcm via pipeline. Around 67% (140 bcm) of that gas was imported by the EU in 2021, with an additional 15 bcm of LNG being imported by the EU from Russia. The aforementioned gas imports from Russia represented 45% of the EU’s gas imports. According to the EU’s energy market report (Q4 2020), Russian pipeline supplies covered 49% of extra-EU net gas imports – nearly double the Norwegian pipeline gas, which was the second most prominent source at 22%. Given the European dependency on Russian gas exports, war in Ukraine has complicated matters on the diplomatic and economic fronts.

Fig.2: Russian Gas Reserves, 1st Jan 2021, Estimated. (Source: EIA)

Sanctions on Russian gas and crude exports will lead to a systemic and skewed shock on the EU. Bruegel, a European think tank, estimates that a phased embargo on Russian crude oil and oil imports will quantify into a sanction of 30% of EU crude oil imports and 15% on oil product imports. This is neither desirable nor optimal. Russia is the EU’s fifth-largest trading partner for exports and third-largest for imports. Any unilateral move for sanctions on imports could mean a retaliation. Recent complete shut-offs for Poland, Finland and Bulgaria illustrate the need for a well-thought-out plan. The REPowerEU aims to make the EU independent of Russian fossil fuels “well before” 2030. The plan includes a diversification from Russian gas imports, tackling rising energy prices and focusing on enhancing EU gas storage in the near term. This also includes a plan to cut dependency on Russian gas imports by two-thirds by the end of the year, which may be costly for Europe given the heavy and rigid pipeline infrastructure already set up with Russia in mind.

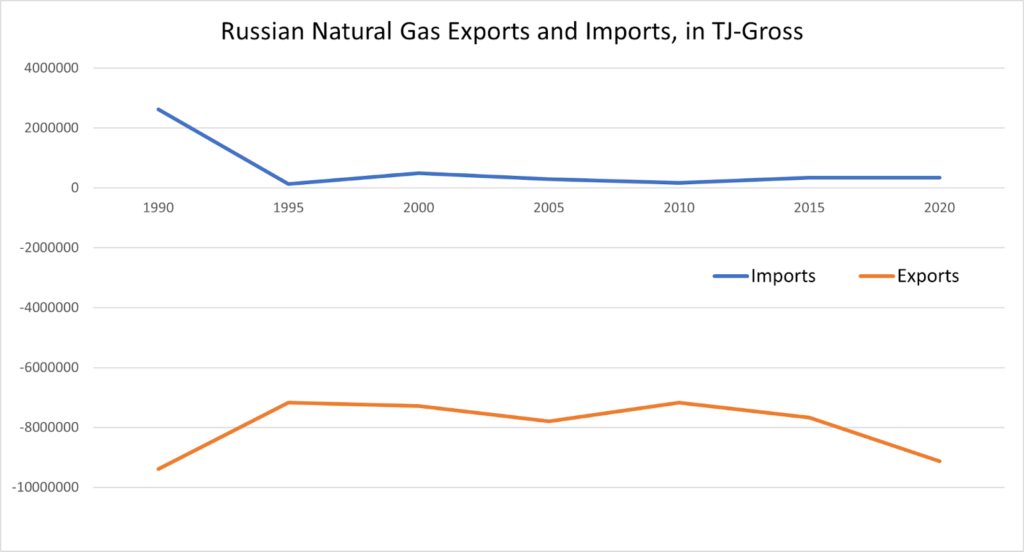

Fig 3: Russian Natural gas Exports and Imports, in TJ Gross calorific value. (Data Source: IEA Natural Gas Information)

Gazprom: A Gas Giant

The Russian gas industry is highly consolidated, with state-owned firms calling the shots on gas production, storage and transportation. Gazprom and Novatek are the largest gas producers, but some oil producers (such as Rosneft) also operate gas facilities. Conversely, gas producers also have oil operations. Despite increasing production from Rosneft and Novatek, Gazprom plays an outsized role in the Russian gas industry. As well as in the global gas markets, accounting for 5% of Russian GDP in terms of sales. In 2021, Gazprom accounted for 68% of Russian gas production. Under Russian legislation, Gazprom has exclusive rights to export natural gas through pipelines via its export wing, OOO Gazprom export (see Fig. 4).

Fig 4: Gazprom company structure. (Source: Gazprom)

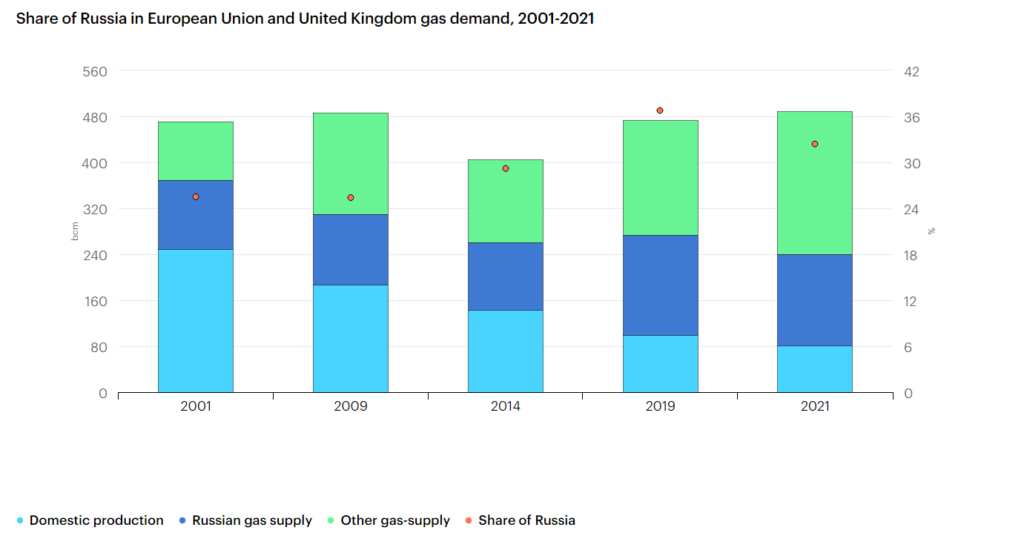

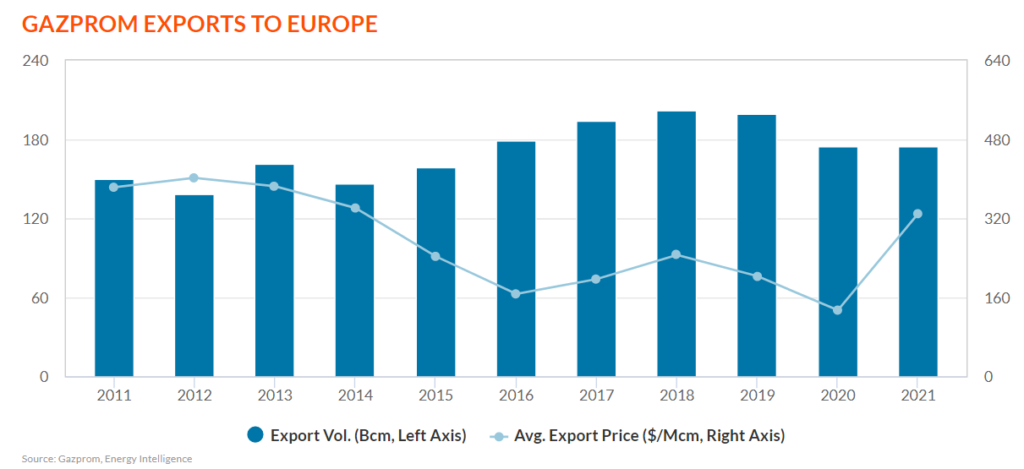

Around 40% of Europe’s gas demand is satisfied via Russian imports (175 bcm, 2021). This share has increased over the past few years, as European domestic production of gas has fallen. Only Gazprom pipeline exports constitute 150 bcm ( 86%, 2021 data) of the total number. To put things into perspective, Gazprom exported 203 bcm via its pipelines in 2021. Top consumers of Gazprom’s gas in 2021 from the EU were Germany, which demanded 45.8 bcm (~33% of German gas imports), Italy, taking in 20.8 bcm (40% of imported gas), and Austria, which received 13.2 bcm (80% of gas imports). The EU is heavily dependent on Gazprom for its gas, while Gazprom is dependent on the EU for a large portion of its revenue. Gas sales to Europe accounted for 70% of Gazprom’s gas revenue in 2019. Russian gas has been increasing its share in the EU and UK Gas demand with its supplies moving from 25% to 32% from 2009 to 2021 (Fig.3).

Fig 5: EU gas imports (Left, in bcm), and Russian share in EU gas imports (Right, in percentage). (Source: International Energy Agency)

A Labyrinthine Network of Pipelines

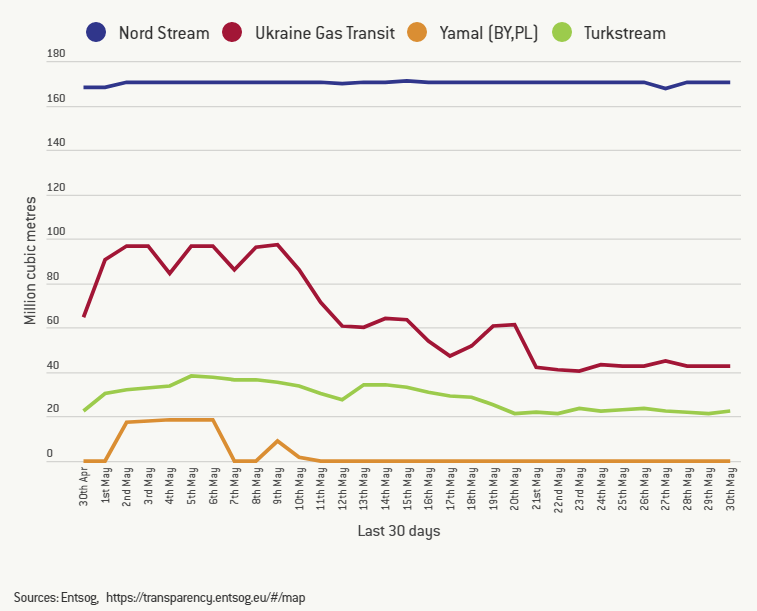

Gazprom owns and operates a vast network of gas export pipelines (see Fig. 8). They are operated by Gazprom’s subsidiaries. The pipelines run via Belarus (Yamal), Ukraine and Poland. While the newly constructed Nord Stream, the Blue Stream and TurkStream import gas directly to Europe. Russia completed the Nord Stream II pipeline in 2021 but was refused certification by German authorities as a result of its military operations in Ukraine. The Nord Stream route was the most important supply route to Europe in terms of transit volume. In Q4 of 2020, 37% of EU Russian pipeline imports (15 bcm) were transported through the system. In addition, 14 bcm (34%) flowed via the Ukraine transit route and 25% (33%) flowed through Belarus. Turk Stream witnessed 4% of total Russian flows to the EU. In 2021, Ukrainian transit flows to the EU and UK reduced to 25%, which was a far cry from 60% in 2009. The Nord Stream has been the go-to pipeline for EU imports of Russian gas, taking up more and more share of the total volume of flows from Yamal and Ukrainian transit lines.

Fig. 6: Daily gas imports by the EU via Russian routes over the past month, in mcm/day. (Source: Breugel)

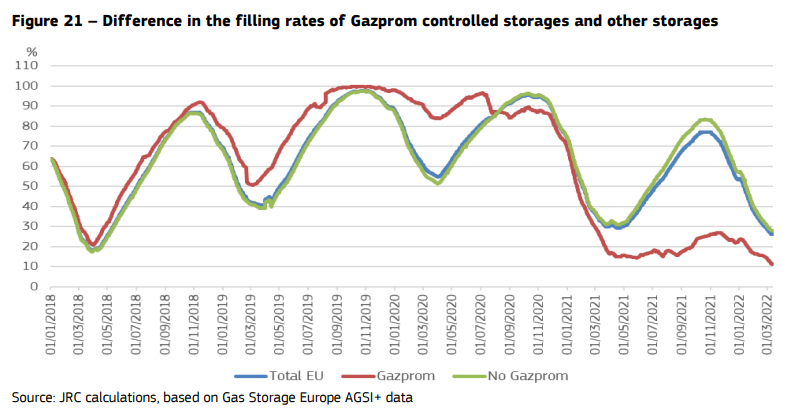

In the first two months of 2022, the IEA noted that despite contractually fulfilling its obligations, Russian pipeline exports to Europe were down from their 2019 level, as well as 37% down Y-o-Y (year over year) in the first seven weeks of 2022. A reduction in pipeline exports was coupled with an inadequate filling of gas storage Russian companies in the EU. Gazprom storage sites account for 10% of EU working storage capacity, and they filled just 25% of their working storage in this period. Gazprom’s filling rate was at 23% in December 2021, compared to the EU average of 53% (See Fig. 7). Gazprom’s activities leading up to the military operations in Ukraine have been atypical. This was highlighted by a 2022 report by the European Commission, which states that- “… besides the global markets, from the summer more and more attention was directed towards the unusual transmission capacity booking practice of Russian gas supplier Gazprom and lower than expected Russian gas inflows, predominantly through the Yamal pipeline and Ukraine. The Russian company referred to the prioritization of filling up storage in Russia during the summer and early autumn months, which could be tracked beside low inflows through the record low gas storage levels managed by Gazprom in Germany, the Netherlands and Austria.” The last pipeline delivery to Germany via the Yamal Pipeline was on 20 December 2021, while gas flows via Ukraine more than halved from an average of 80 mcm/day to 36 mcm/day in the first seven weeks of 2022. Nevertheless, none of these signs could have conclusively foretold the invasion of Ukraine on February 24th.

Fig 7: Gazprom’s filling rates dropped off at the end of the year, contributing to low storage levels across the EU. (Source: JRC, European Commission)

On the one hand, the EU’s structural dependency on Russian gas poses a problem for the energy security of the countries affiliated with the Union. On the other, however, Russia has a structural dependency on the EU for its gas exports. To mitigate concentration risk, recent policy efforts and infrastructural developments have aimed to increase Gazprom’s influence in Asia as a dominant supplier of gas. In 2019, a 3,000 km Power of Siberia pipeline was inaugurated to be able to send a capacity of 38 bcm/year to China, with 10 bcm being exported in 2021. It also announced a Power of Siberia-2 pipeline with a capacity of 50 bcm/year. This will reduce dependency on Europe as a destination for Russian imports, and increase trade flows between China and Russia. This has already been evidenced by a 60% Y-o-Y increase in Gazprom gas flows to China in the first quarter of 2022, while exports to countries outside the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) fell 27.6% Y-o-Y. According to Bloomberg, April’s Russian average daily flows to the borders of European nations were down 18% from March, at 298 mcm/day.

Fig 8: EU Natural gas import routes. (Source: Breugel)

Russian gas flows to the EU may have slowed, but they have not ceased. In fact, since the invasion in February, EU gas purchases through the Russian pipeline increased by 10% compared to the January-February period of 2022. According to the IEA, liquified natural gas (LNG) inflows have increased 63% Y-o-Y from October 2021 to May 2022 to the EU. And are expected to ramp up further, with the USA supplying more than half of the LNG over the period, as the EU attempts to wean off Gazprom’s gas imports. Pipeline suppliers in Algeria and Norway have also increased their yearly flows to the EU. In the short term, Russian gas imports cannot be replaced completely.

At the time of writing, Gazprom has warned counter parties that they should make payments in Russian Rubles or face termination of gas supplies, following a decree from the Russian high command. Refusal to pay in Rubles, among other considerations, has already led to Gazprom discontinuing supplies to Poland, Bulgaria, Finland, Netherlands and Denmark. Despite having multiple long-term Euro or Dollar denominated contractual obligations in multiple countries, this move has exacerbated European worries about being able to have adequate gas in time for the upcoming winter season. Such a mechanism would be made via special Euro and Dollar accounts held by the buyer at Gazprombank, which would buy and transfer Rubles in the name of the buyer to Gazprom. It comes as no surprise that Russia’s third-largest bank is majorly owned and run by Gazprom and its subsidiaries. The European Commission has called for a united front against the call for payments in Russian Rubles.

Despite this, German gas giants Uniper and RWE have complied with Russian guidelines and paid in Rubles. As Russian gas accounts for half of the German fuel imports in 2021, it is critical for the country. Despite the ongoing sanctions, Gazprom reports that half of the 54 companies that have long-term contracts with Gazprom Export had opened Ruble accounts. Gazprom Germania GmbH, which covers Gazprom’s entire German, Swiss and Czech gas-value chain operations, recently discontinued operations in Germany over payment disputes, leaving behind vast swathes of fixed assets, and a risk of a systemic crisis if it reaches insolvency. Germany’s regulators have since then pledged to sustain the operations of the company.

Fig 9: Gazprom’s exports to Europe over the years. (Source: Energy Intelligence)

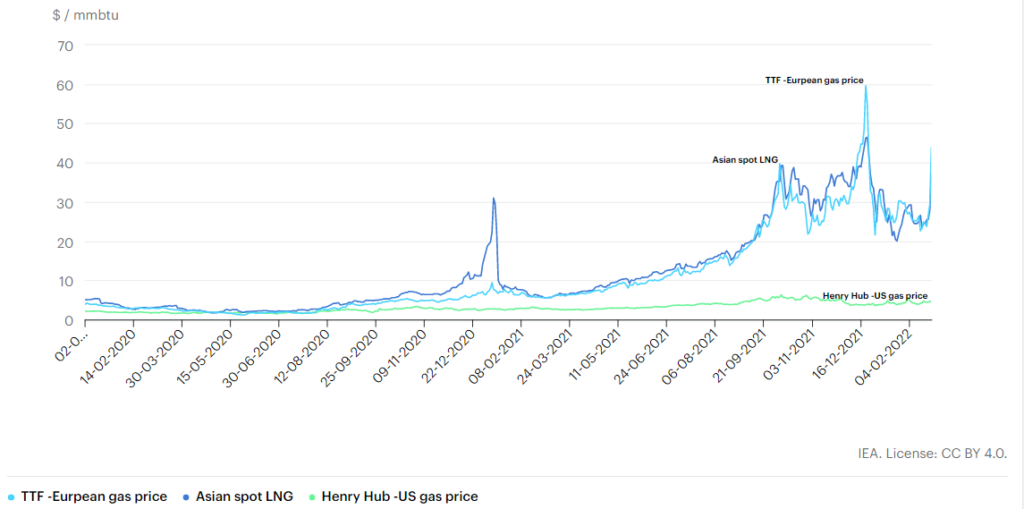

Supply Shocks and Threat of Disruption Have Caused Price Spikes

Gazprom’s pipeline supplies to Europe fell in Q4 of 2021 by 24% Y-o-Y, with Yamal and Ukrainian transit volumes falling 56% and 36% Y-o-Y respectively in the same period, and with Spanish pipeline imports from Algeria falling by 27% Y-o-Y. Higher amounts of LNG imports and low gas storage filling rates (53% in December, a decade low, as seen in Fig. 7) have discernibly put pressure on gas prices in Europe. Industrial gas prices were up 36% Y-oY in Q4 2021, while retail gas prices for households in EU capital cities were up 65% Y-o-Y in February 2022. Overall supply uncertainty and lower storage had certainly put pressure on gas prices in Q4 2021, where prices hovered around USD 30/MMBtu, Russian invasion on May 24th caused D-o-D (day-on-day) European gas prices to spike by 50%, to 44 USD/MMBtu(see Fig. 10). Global gas prices will remain elevated till supply-side concerns are alleviated in the near term, according to the general consensus.

Fig 10: European gas prices spiked after the Russian attack on Ukraine on Feb. 24. (Source: IEA)

A New Order

Despite launching a cascade of sanctions, which will eventually lead to systemic shifts from Russian fossil fuels by the EU, near-term volatility of gas and filling the supply void left by reduced Russian export reductions will remain a key concern for the EU. According to the BBC, 40% of EU gas and 27% of EU oil are imported from Russia, for an annual bill of 400 billion Euros. Sanctions can hurt Russia economically, and Gazprom could bear a large brunt of this cost. Europe-wide boycotts of Russian fossil fuels have led Gazprom to redouble its efforts to increase gas sales to China and India. Re-routing of gas to India, China, and Egypt has taken place, sometimes with steep discounts. Since the invasion, CERA estimates that deliveries to non-EU countries of crude oil increased by 20%, of coal by 30% and of LNG by 80%.

Experts also believe that the green energy transitions and shifts away from reliance on Russian gas can cause Gazprom to lose a third of its gas exports to Europe. This may lead to newer players entering the market to fill the void. According to 2021 figures, 15 bcm worth of contracts is expiring in 2022, which account for 12% of Gazprom’s exports to the EU. By 2030, the IEA suggests that 40 bcm of contracts with Gazprom will run their course. Energy Intelligence believes that Gazprom’s target of sending 70% of its gas exports to Europe by 2030 may no longer be “realistic,” and that this may cause the company to rethink its policy. It remains to be seen whether this trend will lead to an emergence of a new alternative for the bulk of Russia’s gas and oil exports, though the CERA believes that to be less likely in the short term.

Amineh and Crijns-Graus, in their 2018 paper, highlighted the “structural scarcity” that the EU could be facing by the “deliberate action of a major power or non-state actor, such as a major oil company”. They cite the example of the Russo-Ukrainian gas crisis of 2009 as an archetypal example of Gazprom’s strength in global gas markets, where it simply shut gas pumps and induced gas shortages in 18 European countries. A similar tale seems to be unfolding in 2022, where Gazprom has an instrumental role to play in executing the Russian state’s bidding. This is bound to make Europe jittery and has led to seismic shifts in energy policy. In a nutshell, Gazprom is not as clandestine as it seems, and actions by the colossal corporation have an asymmetric role to play in global economic operations.