By Ollie Campbell, PPE Student at Warwick University

As a result of the Covid pandemic, 2020 saw the biggest decline in the global economy since WW2. The global GDP declined by 3.4% in 2020 and the GDP of the OECD countries declined by 4.9%, but the bounce-back seems to have caught several economic forecasters on the hop. Despite that reasonable decline for the OECD countries, which only increased in the first quarter of 2021, the 38 developed countries surpassed their pre-pandemic GDP level at the end of 2021’s third quarter. On a global view, it looks like smooth sailing for most countries as unemployment is at a comfortable rate and if anything, there is a labour shortage in many developed countries, something unexpected post-recession. Even after several variants have swept across the world, creating new peaks in COVID-19 case numbers, aggregate household income is above pre-pandemic levels around most developed countries. But this conceals the devastating inequality across the world as some countries have struggled to rebound much more as different government strategies have caused disparities in economic growth.

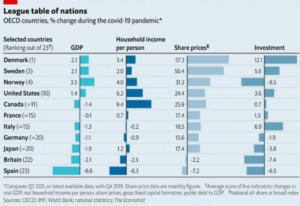

The Economist has analysed data across 23 developed countries to highlight the differences in COVID economic response, some of which are shown in the table below:

From this, we can see that there are huge differences between Scandinavian Europe and the rest of Western Europe, as Germany, Britain and Spain bring up the rear. The current forecast only suggests that this will exacerbate as investment and share prices are where there are the greatest differences, and this is arguably the best tool for future economic prediction.

Now there are obvious reasons behind the substandard economic performance for Southern Europe, mainly the reliance on tourism. Due to the travel bans in place, economies that are hugely dependent on tourism have suffered, such as Spain, France and Italy who are all in the lower half of the 23 economies. Consequently, these economies have had to borrow more to afford Job retention schemes due to the high unemployment without tourism. The faster a country has been able to adapt to the life of working from home, the less needed to be spent on furlough and henceforth greater investment flexibility.

Where Governments have funnelled finances has possibly influenced economic bounce-backs the most. The US has had a fairly unique approach of donating large sums to the population in the form of stimulus packages, totalling over $2trn across the pandemic. In contrast, the Baltics and most of Eastern Europe have focused their spending on helping firms cashflow or expanding healthcare capacity all worthwhile programmes. However, it seems some countries, such as Austria and Spain, have managed to achieve nothing as their policy has hardly preserved jobs or even compensated the unemployed. As a result, they have suffered greatly economically Spain coming last out of the 23 countries when its GDP is higher than several of the countries analysed.

Something that has to be incorporated is how well the stock market of a country is doing, from which we can infer the amount of money the country and population have to invest as well as how profitable the companies are mid-pandemic. Britain’s stock market has quite clearly suffered as the average investor has less disposable income for investment and as a mature market, there are few start-ups/ quick growth companies in comparison to the US. Since the pandemic and the rise of Bitcoin, most investments have been made into cryptocurrencies and NFTs, another reason for the faltering stock markets.

However, some markets are soaring, especially those in Scandinavia. Denmark has three healthcare companies in its top ten stocks, a sector that is obviously profitable during a pandemic. It is of no surprise that there has been active growth in the OECD economies because the pandemic has provided a perfect opportunity for entrepreneurs to utilise the recession to grow big. There are big forecasts by Goldman Sachs for the S&P 500 for 2022, with a large focus on CAPEX and research with hopes for large growth in multiple important sectors.

A hugely important factor for judging government response to Covid economically is government indebtedness. Most countries around the world have increased in debt dramatically as governments take any funds possible to help with pandemic recovery. The UK, US and Canada have all racked up a comfortable size debt, which would be expected from a recession. Now, this clearly is a threat to the economy as a tax hike is to be expected and potential austerity from spending reductions. Sweden has managed to amass a much lower level of debt from the pandemic as it only rose by 6% at its peak which may well be a reflection of the fact that Sweden managed to mostly avoid strict lockdowns necessitating less need for fiscal support.

Covid has by no means gone. The omicron variant has seen case numbers rise to the highest they have ever been, but fewer lockdown measures have been put in place. This would suggest that Covid will curtail growth in the early stages of 2022, but economies should remain in positive growth for the whole year. The OECD predicts that the stragglers will catch up as they grow at increasing speeds over 2022, such as Spain and Italy growing 5.5% and 4.6% respectively. There will still be large differences as the top three OECD economies are expected to have a combined GDP of 5% more than the pre-pandemic level when the lowest three economies will only be 1% higher. This is likely to have a huge impact on post-pandemic economic change worldwide.

Ollie Campbell

I’m Ollie Campbell, a current undergraduate PPE student at the University of Warwick. I am interested in political journalism and analysis especially on the economic side. As an aspiring politician I spend a large amount of free-time studying the workings of politics and am a member of the Conservative groups both at Uni and at home.