By Stephanie Kannimmel, Contributor to TheLF

COVID-19 has had a significant impact on welfare states across the developed world. To account for the damage caused by the pandemic, governments responded by making welfare state policies vastly more generous. However, considering that welfare state retrenchment has occurred to a degree in many mature democracies, many may wonder whether the COVID-19 welfare state is here to stay.

COVID-19’s effect on social policy in mature democracies

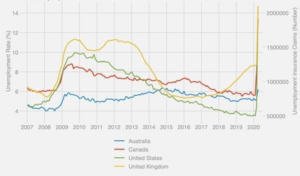

Governments in the developed world responded to COVID-19 by making social policies more generous. Historical parallels suggest that this may endure. For example, during World War II, governments across the developed world increased welfare state coverage and the value of payments received as people demanded more social insurance in the face of risk and uncertainty. However, due to forced closures of businesses and schools, the impact of the economic crisis caused by COVID-19 is much worse than previous recessions. Increases in unemployment rates have literally gone off the old charts, as seen in the figure below:

Figure 1: Unemployment Rates (AUS, CAN, US) and Unemployment Insurance Claims (UK)

Source: Our World in Data

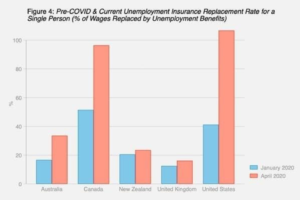

As developed countries increase social spending, attitudes towards redistribution are also shifting. In the UK, citizens are now more likely to say that social policy is too stingy compared to previous claims that people were free riding off the welfare state. In contrast to the 2008 financial crisis where the impact was concentrated among low-skilled workers, COVID-19 had a much wider impact. Shutdowns meant an increase in unemployment across skill levels, meaning that governments had no choice but to increase the generosity of the welfare state in this case. Social safety nets in many developed countries proved not to work even before COVID-19 as unemployment soared. These adverse effects were compounded by rising healthcare and pension costs. As a result, governments increased benefits significantly in a matter of months at the start of the pandemic:

Figure 2: Pre-COVID and Current Unemployment Insurance Replacement Rate for a Single Person (% of Wages Replaced by Unemployment Benefits), 2020

Source: Australian Government, Government of Canada, Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (US), Department for Work and Pensions (UK)

Predictions for the future of the welfare state

COVID-19 has taken a toll on people’s ability to work across the income distribution. It also poses more widespread risks than in previous recessions, such as health risks leading to increased demand for sick pay among workers. Given the universal risk COVID-19 presents, it may seem more likely that a more generous welfare state will persist after the pandemic. However, this depends on two main factors. Welfare states will only permanently become more generous if voters believe that COVID-19 will pose an enduring risk to their incomes, and if they align their interests with individuals that are the worst affected by the pandemic.

Previous recessions show that increases in welfare state generosity do not necessarily continue over the long term. The 1970s marked the end of the Golden Era of the welfare state after World War II due to technological advances, demographic change, globalisation, automation, and trade destroying mid-skill manufacturing occupations. Because high-skilled workers did not see the need for an expanded welfare state, and the lower-skilled population was too small to make a difference in elections, governments now had little electoral incentive to be generous with social policy. Similarly, the impact of the 2008 financial crisis was concentrated among low-skilled workers. As a result, governments did not increase the generosity of the welfare state in response.

The universal impact of COVID-19 across social classes may suggest that governments will continue to be electorally incentivised to pursue welfare state expansion. However, this may not necessarily be the case. Despite the pandemic taking a toll on people across the income distribution, economic and health risks have been and will continue to be the most severe for the poor. Thus, it is not guaranteed that high-skilled workers will still demand higher social insurance payments after the pandemic due to the prioritisation of concern with their own incomes over affinity with the worst affected.

Despite the potential for welfare state retrenchment to occur after the pandemic, welfare state expansion looks to be a greater possibility. Retrenchment has not occurred to a large extent except in a handful of mature welfare states where an ageing population and declining productivity in the shift from manufacturing to the service sector has emerged. Unemployment benefits and stimulus packages provided during the pandemic have led to increased replacement rates and greater demand for social expenditures. Furthermore, increased demand for social policies are also occurring in mature democracies for concerns other than unemployment and healthcare. Ageing populations and changing household structures that entrust social care to institutions other than the family have led to increasing demand for pensions, childcare, and elderly care.

Despite the promise of enduring social policy generosity after COVID-19, conflicts exist in terms of increased demand for social expenditures during the pandemic versus fiscal pressures already in place that compromise governments’ abilities to spend more. In countries such as Germany and Japan that face domestic issues directly linked to welfare state retrenchment (i.e. ageing populations and declining productivity growth), it is more difficult to predict whether welfare state expansion or retrenchment will occur in the long run. Ultimately, the question of which one will win out depends on the political and social norms of each country. This includes the type of society voters want to live in and the types of parties they vote for in the broader context of what is feasible. Therefore, for social policy generosity to persist after COVID-19, governments need to be creative in how they finance the welfare state and deal with fiscal pressures.

Will this be different in developing countries?

Although social policy generosity looks to be on the rise in mature democracies, the impact of COVID-19 on the welfare state is likely to be different in developing countries. One reason for this is that incentives for electoral outcomes may be different in countries experiencing issues such as corruption and dictatorship. Furthermore, different proportions of high-skilled and low-skilled workers are present in developing countries.

Developing countries may also not have the resources to create an affordable and sustainable welfare state, especially given the damage caused by COVID-19. To create such a welfare state and expand generosity, governments face risks of stretching public finances, distorting incentives, and creating rigid societies. This may not be possible for developing countries that are unable to use technology to make their bureaucracies more efficient, spend large portions of GDP to maintain labour market flexibility in retraining and advising the jobless, and create safety nets for gig workers and the self-employed.

Although it might be risky for governments of both developed countries and mature democracies to expand social policy generosity, they should ultimately take a long-term measured view on social policy spending in any way that they are able to. This can include implementing affordable safety nets and mechanisms that cushion people more effectively against job loss and income shocks. Governments do not have to aim to eliminate risk entirely but should help ensure that people are able to bounce back in the event of shocks such as those posed by the pandemic.

Further reading:

- https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-has-brought-the-welfare-state-back-and-it-might-be-here-to-stay-138564

- https://www.economist.com/leaders/2021/03/06/how-to-make-a-social-safety-net-for-the-post-covid-world

- https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/coronavirus-welfare-state-covid19/

Contributor to The London Financial

We combine research produced by students and early professionals into a single website, breaking down the barriers to entry individuals face in a number of industries.

Contributor opinions are their own and do not necessarily reflect the stance of the LF.

Thank you for sharing superb informations. Your web site is very cool. I’m impressed by the details that you’ve on this website. It reveals how nicely you understand this subject. Bookmarked this website page, will come back for more articles. You, my pal, ROCK! I found simply the information I already searched all over the place and simply could not come across. What an ideal site.