By Claire Contri, Editor-in-Chief at The London Financial

Over the years, the threat of climate change and environmental degradation has caused organizations to mitigate and reverse these trends worldwide. Governments, corporations, NGOs, researchers, and citizens are increasingly trying to collaborate to find common grounds to improve the overall situation without compromising the global economy or their personal satisfaction. Among others, finance has been one of the solutions proposed. Despite criticism of significant banking institutions and the finance industry, a new way of ‘green’ investing has emerged. As the 18th edition of the G20 is about to begin, political decisions are becoming crucial to determine the fate of humanity. Hence, the next few years will be critical to ensure the financial system is fit for purpose to deliver the financing needed to achieve environmental and other SDGs.

2023, or The Planet’s Hottest Decade Ever Recorded

Despite progress, atmospheric CO2 concentrations continue to increase. Global average temperatures in 2023 are forecasted to be the hottest, capping the planet’s hottest decade. To prevent the world from a global humanitarian and economic disaster, carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions will need to be reduced by about 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030, reaching ‘net zero’ around 2050. The ‘decade of action’ in support of climate and other sustainable development goals (SDGs) has begun, but much remains to be done.

After the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020, a return to “business as usual” and environmentally detrimental investment activities must be avoided, and the world must commit to building back its economy responsively and stepping up actions for a sustainable and inclusive recovery. Countries and regions have already made significant steps towards that, namely, South Korea’s Green New Deal or the European Green Deal.

Thus, achieving climate objectives requires an unprecedented acceleration of financial flows into climate-aligned investments and a massive shift away from investments in emissions-intensive activities. Indeed, according to the OECD, in their 2017 Investing in Climate, Investing in Growth report: “Finance will be a key factor [where] capital must be mobilized from both public and private sources, supported by a variety of financial instruments tuned for low‑emission, climate-resilient infrastructure. Public financial institutions must be geared for the transition, while the financial system should take greater steps to value and incorporate climate‑related risks correctly”.

The Problem With the Banking World Today

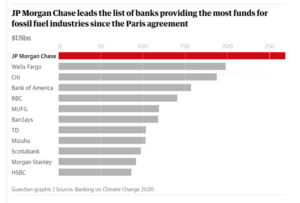

According to a study published in 2020 by Rainforest Action Network, BankTrack, Indigenous Environmental Network, Oil Change International, Reclaim Finance, and Sierra Club, the world’s 35 largest investment banks have funneled more than $2.66tn into fossil fuels, an increase of 40% in 2020 since the Paris agreement. Moreover, despite Glasgow’s 2021 COP26 goal of making the business and the banking sector focus on tackling the climate crisis, the 2023 Banking on Climate Chaos report emphasized that the world’s 60 biggest banks have now provided $4.6 trillion in financing for fossil fuels since the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Alison Kirsch, a researcher at Rainforest Action Network who led the analysis in the report, declared: “The data reveal that global banks are not only ramping up financing of fossil fuels overall but are also increasing funding for the companies most responsible for fossil fuel expansion.”

Kirsch also declared: “This makes it crystal clear that banks are failing miserably when responding to the urgency of the climate crisis. As the toll of death and destruction from unprecedented floods, droughts, fires, and storms grows, it is unconscionable and outrageous for banks to approve new loans and raise capital for the companies pushing hardest to increase carbon emissions.”

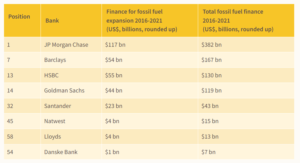

Below is a table showing the banks investing the most in fossil fuels. Again, between 2016 and 2021, JP Morgan led the other banks in financing fossil fuel expansion.

Source: Banking on Climate Chaos

Why is this such a problem? Banks provide financial services (loans, insurance, and other forms of financing) to fossil fuel companies. Investing in those companies encourages them to fund high climate impact industries, such as extracting more coal and burning more oil, which drains enormous amounts of greenhouse gas into our atmosphere. Furthermore, banks can fund projects like expanding a coal mine or constructing a new oil rig. Without their money, projects like these would not be able to take place. Another example includes banks financing projects that can harm communities and human health. For instance, a study found that companies funded by UK banks are behind some of the worst environmental abuses. Indeed, they were found to be responsible for financing 805 million tonnes of CO2 in 2019, making London the 9th most significant emitter of CO2 in the world if it were a country.

Banks shape our future while investing in sustainable or non-sustainable projects. Thus, banks can drive us into a fossil fuel-dependent future or turn us towards a greener one. For example, banks, including HSBC, Barclays, and Santander, have supported the expansion of the Cerrejón coal mine in Colombia. Some of the project’s negative impacts include dislocating multiple Indigenous communities from their habitat. At the same time, those living in the area face severe droughts fuelled by the mine’s enormous water extraction. As the 2023 Banking on Climate Chaos report warned: “Bank funding for fossil fuels often brings dire threats to the lives and livelihoods of local communities around the world — harming Indigenous Peoples, Black and Brown communities, and poor and working-class communities first and worst.”

Another example of banks implicated in human rights abuses includes those who invested more than €24.2 billion ($26.05 billion) in 11 global arms companies supplying weapons in Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen conflicts, according to the DIRTY Profits 7 report. Lloyds Bank was one of the two largest overall providers of loans to the arms companies, totaling €4.1 billion ($4.41 billion). Regarding actual shareholdings in the arms companies, Deutsche Bank ranked second among all the banks, with holdings in all arms companies totaling €2.6 billion ($2.8 billion). Banks such as Barclays and Santander were also named in the report.

Therefore, despite a growing number of financial institutions pledging their green commitments, facts show that many, if not all, still have interests in investing in fossil fuels and projects that negatively impact the environment and its communities. The financial sector has a vital role in the fight against climate change by supporting reductions in climate change risk and mitigating the impact of adverse climate events. Banks investing heavily in fossil fuels could have contributed to a better world by funding projects building renewables and batteries, developing new electric-powered arc-steel furnaces, or helping to pay for a phase-out of coal and gas power plants, among many examples. But by sponsoring unethical actions and projects, banks are sending a message to the rest of the banking community: as long as fossil companies want to keep destroying the climate upon which we all depend, banks and finance will support them.

What is Green Finance?

As many banks and the financial industry are generally accused of worsening climate change, how can we find ways to use finance as a force for good to accelerate environmental and social transition? One solution is using green finance.

Green finance has many names, definitions, and subcategories. Here are some of the most common ones:

- Green Finance: The easiest way to define Green Finance is to consider it an investment supporting environmentally-friendly activities, such as purchasing goods and services or building environmentally-friendly infrastructure. It involves collecting funds for addressing climate and environmental issues.

- Greening Finance: Greening Finance is short for ‘greening the financial system’ and corresponds to the diffusion of new tools, procedures, and regulations aimed at inducing the financial system to take due account of climate and environmental considerations in financial risk management and, consequently, investment decision-making.

- Climate Finance: As discussed in COP26, climate finance is a subset of green finance. It refers primarily to public finance, or where developed countries provide financing through various sources that promote multilateral efforts to combat climate change. Green finance is a broader term encompassing all financial flows supporting sustainable environmental objectives.

- ESG Investing: ESG Investing, also called Sustainable Finance, refers to the environmental, social, and governance criteria for evaluating corporate behavior and screening potential investments. The ESG evaluation supplements traditional financial analysis by identifying a company’s ESG risks and opportunities: the money they stand to lose by not acting on ESG risks and the money they stand to gain from seizing ESG opportunities. Nonetheless, financial returns remain the primary objective of ESG investing.

The table below lists some commonly considered ESG factors.

Source: Investopedia

- Impact Investing: Impact investing refers to investments made into companies, organizations, and funds to generate a measurable, beneficial social or environmental impact alongside a financial return. An example of an impact investing initiative includes the 2012 Morgan Stanley Investing with Impact platform, which clients can use to invest their money in opportunities that bring profits and create positive change. The investment opportunities on the platform are diverse and cover over 30 issue areas. It incorporates ESG criteria alongside financial projections so clients can get the returns they want without contributing their dollars to companies and projects negatively impacting the environment.

- Socially Responsible Investing (SRI): Last but not least in this list is SRI, which eliminates or adds investments based solely on a specific ethical consideration. For example, an investor might avoid any mutual fund or exchange-traded fund (ETF) that owns stocks of firearms manufacturers. Alternatively, an investor might seek to allocate a fixed proportion of their portfolio to companies that donate a high proportion of their profits to charitable causes. Socially responsible investors might also avoid companies associated with alcohol, tobacco, and other addictive substances, gambling, weapons production, human rights and labor violations, and environmental damage.

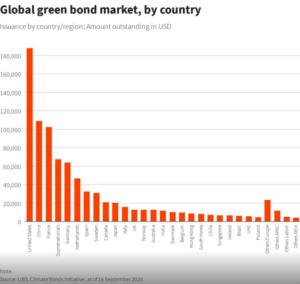

Hence, different means exist to catalyze sustainable and responsible investments. Among the most common green investment solutions are privately placed green bonds, renewable, sustainable equity, green mutual funds, solar bonds, mortgages, credit cards, stocks, and renewable energy credits. Today, Green Finance is blossoming as globally, the green bond market is expected to reach $2.36 trillion in t2023. In 2020, the US, China, and France were the three biggest issuers of green bonds.

Source: World Economic Forum

How Can Green Finance Deliver Real Environmental and Climate Impact? What are the Challenges Associated With Such a Shift?

Green finance can provide economic and environmental benefits to all and must be managed to ensure a just transition to a low-carbon society. In such a way, green financing expands the number of individuals and businesses who can access environmentally-friendly goods and services, especially for the vulnerable and marginalized. This makes the transition to a low-carbon society more equal, creating more socially inclusive growth. It means more money is invested into businesses to help them become greener. This can help businesses grow, creating jobs, reducing carbon emissions, and stimulating the economy, creating what Lloyds calls a ‘great green multiplier’ effect where the economy and environment continuously benefit.

Source: Lloyds

In short, the benefits of green finance include producing a competitive advantage as it tackles the challenges linked to climate change while adding business value to companies by increasing and advertising their participation in green financing. In return, it offers businesses a green edge, attracting more environmentally concerned investors and customers, increasing overall ROI and environmental and social impact. Lastly, Green Finance can enhance economic prospects by building and encouraging local markets to invest in sustainable projects such as renewable energy or biomimicry infrastructure while entering new sustainable markets with high employment potential.

However, shifting to a low-carbon economy will not be an easy task. It will require significant investments, which can only be funded through heavily private-sector engagement and inter-sector and international cooperation. As mentioned, incorporating ESG factors into private investments will transform many risks linked to climate change into drivers for innovation that will provide long-term value for companies and society. Nonetheless, capital mobilization for green investments has been constrained due to several obstacles, including maturity mismatches between long-term green investments. Additionally, the typically short-term mentalities of investors who want immediate and high ROI also impact capital mobilization. Furthermore, financial and environmental policies are not always implemented and integrated into companies’ operations. Most significantly, a standardized definition of ‘green investing’ and appropriate taxonomy policies of green activities are required to assist investors and financial institutions in allocating money effectively and make educated judgments. Furthermore, financial and extra-financial disclosures must be more than voluntary but mandatory to assure companies’ compliance with the laws, regulations, and internal targets. Lastly, customers and governments must tackle growing corporate misinformation issues regarding businesses’ sustainability strategies.

The Paradox of Green Finance: Greenwashing

The recent rise of ESG and its incorporation into companies’ business models also means the rise of unsustainable and unethical ways of promoting business practices.

The most common one is Greenwashing. According to ESG Today, “Greenwashing is a practice used by businesses to represent themselves as more sustainable than they truly are. Whether it’s providing misleading information regarding a product’s sustainability or labeling a fund as “green” when it is not, greenwashing erodes trust and can have significant repercussions. Greenwashing is not a static concept – it occurs on a spectrum, ranging from outright deceit to wishful thinking.”

There are many ways a company can take part in greenwashing. Here are exhaustive examples:

- Greencrowding: Greencrowding involves adopting an environmental group initiative and moving at the speed of the slowest adopter of sustainability policies. For instance, 65 companies have signed up for the Alliance to End Plastic Waste (AEPW) “to end plastic waste in the environment and protect the planet.” The issue? Members range from Big Oil giants like ExxonMobil and Shell to plastic packaging companies like Sealed Air and household names like PepsiCo. Moreover, most members are also in the American Chemistry Council (ACC), which lobbied to weaken the UN’s global treaty on plastic pollution.

- Greenlighting: Greenlighting is when a company spotlights a green feature of its operations or products. This tactic aims to draw attention away from environmentally damaging activities conducted elsewhere. For example, greenlighting is rampant in the car industry, with manufacturers like Toyota promoting massively electric vehicles while this segment makes up a minuscule fraction of the company’s overall production.

- Greenshifting: Greenshifting is when companies imply that the consumer is at fault and shift the blame onto them.

- Greenlabelling: Greenlabelling is a practice where marketers call something green or sustainable, but closer examination reveals this as misleading. For example, an advert for Unilever-owned washing detergent brand Persil was banned last year for doing exactly this.

- Greenrinsing: Greenrinsing refers to a company regularly changing its ESG targets before they are achieved. For instance, Coca-Cola is known for missing and moving its recycling targets and packing them with caveats. As an example, between 2020 and 2022, the company dropped its target for using recycled packaging materials from 50% by 2030 to 25%.

- Greenhushing: Greenhushing is when organizations deliberately choose to under-report or hide their green or ESG credentials from public view to evade scrutiny. Blackrock and HSBC have been accused of this in recent months. The asset management firms downgraded a number of Article 9 funds, exclusively invested in sustainable assets, to an Article 8 category: “funds that promote environmental or social factors but do not need to target a sustainable outcome.”

One of the most notable and scandalous examples of a company openly greenwashing its operations is the 2015 Volkswagen case, where the company admitted to cheating on its emissions tests in the US. What happened is that VW has had a significant push to sell diesel cars in the US, backed by a massive marketing campaign vowing its cars’ low emissions. However, VW later admitted that about 11 million cars worldwide, including eight million in Europe, are fitted with the so-called “defeat device” that emitted nitrogen oxide pollutants up to 40 times above what is allowed in the US. As a result, VW had to pay a total of 31.3 billion euros ($34.69 billion) in fines and settlements, while the former CEO of VW, Martin Winterkorn, had to resign after he lost all trust of his shareholders. More recently, in 2022, Innocent Drinks advertised their ‘eco-friendly’ packaging. The problem? The Coca-Cola group, aka the worst plastic polluter in the world, owns Innocent Drinks, and it turned out that Innocent’s drinks were made of single-use plastic – which is terrible for the environment. One of the outcomes for the company is that it saw its ads banned in the UK, while it drastically tarnished its global reputation as a sustainable and eco-friendly brand.

How Governments Are Cracking Down On Greenwashing

As a result, investors, customers, and governments are all on high alert to counter greenwashing. For example, regulators worldwide have proposed rules designed to drive strategic action around ESG, raising the standard for ESG reporting. In the USA, for instance, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has proposed a policy requiring investment funds to have at least 80% of assets in a fund to reflect its name and cut down on the use of misleading ESG terminology.

In the E.U., the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) is taking steps to improve the transparency and comparability of ESG in financial products such as funds. Through its classification system, a fund can be labeled “standard,” “promoting,” or “having the objective of,” enabling investors to compare funds better and analyze the ESG-related impacts of the investment, known as Principal Adverse Impact indicators.

Last but not least, in the United Kingdom, the Sustainability Disclosure Requirements is a package of reforms requiring companies to implement the Green Taxonomy, follow recommendations from the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, and, subject to consultation, the International Sustainability Standards Board. The reforms also include guidance for transition planning and private company disclosures.

What we can conclude from these case studies is that the consequences of engaging in these greenwashing behaviors can be severe. Instead of advertising fake environmental actions, companies should spend their time and money on shifting their business model and corporate practices to more sustainable ones. Brand reputation is at stake, as is business opportunity.

Concluding Remarks

Therefore, addressing climate change will require a significant increase in green finance and investment when traditional investment falls sharply. Achieving the objective agreed upon in the Paris Agreement (limiting global temperature increases to well below 2°C from pre-industrial levels) requires all forms of finance, whether private, public, or blended finance. Mainstream private finance is particularly indispensable to help companies realign their business models towards net-zero emissions pathways. We must not forget that sustainable growth also means inclusive growth. Coherent climate and investment policies, adequate fiscal and structural policy settings, and reforms must work together to facilitate the transition of exposed businesses and households, particularly in vulnerable regions and communities. In this case, international cooperation remains fundamental to managing climate risks and preventing the worst from happening. Companies and governments must also fight against the threat of greenwashing to ensure that the actions implemented are good for the environment and society. Last but not least, early planning for the transition is essential if societies are to avoid stranded assets in fossil‑fuel‑intensive industries and stranded communities alongside them.

Claire is a French-American Senior at ESSEC Business School in France. She has already done several internships in finance and loves writing articles. She also has a strong interest in sustainable finance and firmly believes that business can be a force for good and lead to positive change. Claire also serves as the Editor-In-Chief of The London Financial. Last but not least, she enjoys meeting new people from different backgrounds and experiences the most!