By Harry Toube, Economics Undergraduate at King’s College London

2023 has been a poor year for observers of the Chinese economy. After the long-awaited end to Dynamic Zero Covid, China watchers expected the country to return to its trend-high growth rate. Instead, despite comprehensive opening up, Chinese growth has been sluggish. Instead of accounts of recovering industries and economic triumphs, we have seen reports of slow consumption growth, a flagging construction sector, and the bankruptcy of major construction firms like the China Evergrande Group. This poor performance has led many observers to suggest that China may be entering its first “Balance Sheet Recession”. In this paper, we will outline the mechanisms underpinning a Balance Sheet Recession and consider whether China is entering into one. Ultimately we find that China exhibits several early warning signs of a Balance Sheet Recession, but is unlikely to have passed the threshold into full-fledged crisis. Moreover, should such a recession materialise, Chinese fiscal policy will likely be well-equipped to mitigate its more severe consequences.

What is a Balance Sheet Recession?

The Balance Sheet Recession is a model of financial crises developed by Japanese economist Richard Koo in response to the exceptionally slow recovery of the Japanese economy from the crisis of 1991. The model offers insights into a rare class of financial crises in which the economy experiences both abundant access to credit and a significant shortage of willing corporate borrowers. Koo criticises standard recession models for taking the willingness of firms to take out loans as a given. Instead, he explains The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics and The Other Half of Macroeconomics focused on the structural effects of micro-level financial sector behaviour.

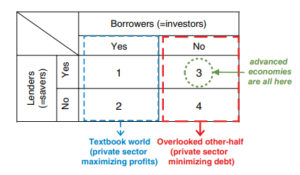

At the heart of the model is the separation of the economy into four basic types: 1) Abundant Borrowers, Willing Lenders, 2) Unwilling Borrowers, Scarce Lenders, 3) Willing Borrowers, Scarce Lenders, and 4) Unwilling Borrowers, Willing Lenders. The type that the economy falls under will determine the nature of its recession and the path for its recovery. These types are illustrated in the table below:

Source: Richard Koo

At the beginning of a Balance Sheet Recession, the economy falls under Type 1 with banks who are willing to make loans, and firms and households who are eager to take them out. Under these ‘ordinary’ circumstances, firms are likely to be highly leveraged and to enjoy high cash flows. However, as history has shown, these booming economic conditions can produce economy-wide asset bubbles. When the asset bubble eventually pops, highly leveraged firms will be left with liabilities priced at the peak bubble level, but assets deflated to the post-bubble norm. Consequently, these leveraged firms will suffer from extremely high levels of debt and exhibit significant holes in their balance sheets. At the same time, banks that were invested directly or indirectly in this asset bubble will be struck with a large number of non-performing loans. These banks lack the capital to make cheap loans and are unwilling to issue them in these uncertain economic conditions.

The model at this point should feel fairly familiar. However, it is here that Koo’s theory departs from standard macroeconomic reasoning. Instead of assuming that the primary problem in a financial crisis is the credit crunch initiated by unwilling lenders, Koo suggests that this crunch is accompanied by the structural presence of firms that are now focused entirely on paying down their recently acquired debt. These firms, Koo argues, will have no interest in taking out loans – even if banks were willing to extend them. If the focus of corporate decision-making is on eliminating the massive liabilities that make firms technically insolvent, then no rational corporate advisor would choose to take out new loans. Crucially, even if loans were issued with 0% interest, it would still not be in the interest of the private sector to take them on. Inevitably, the economy moves into Type 2: The credit crunch prevents banks from issuing loans and the balance sheet holes prevent firms from taking them on. High consumer debt, widespread bankruptcy, rising unemployment, and the general lack of credit depress aggregate demand and create low cash flows for firms.

In many ways, these outcomes are typical for a depressed economy. Eventually, the government intervenes with bank bailouts and monetary easing to clean up the financial trouble in the banking sector. To some degree, household consumption may recover and the consumption component of aggregate demand may even return to normal. However, even with high corporate cash flows, firms are still primarily concerned with the long process of paying back their debt. Rather than creating a wave of investment, these increased cash flows are overwhelmingly transferred into higher corporate savings. Because of the importance of restoring financial health, firms will neither invest out of profits nor take out loans to fuel investment. The economy has moved into Type 4: credit is abundant, but firms are unwilling to borrow.

This outcome is paradoxical. The economy may have strong consumption data, productive, efficient, and profitable firms, a large trade surplus, zero interest rates, and an abundance of willingly extended loans. Yet, it still registers near-zero investment, massive net private-sector savings, and deflation. Standard government efforts to fix the problem also fail. Monetary policy is entirely impotent since the problem lies with demand for, not supply of, credit. The problem of structural saving renews the importance of Keynes’ Paradox of Thrift. As each firm saves to improve its financial health, the economy as a whole experiences enormous leakage from its circular flow of income. Bank reserves increase, but these saved funds have no outlet for domestic investment. Without government intervention, economy-wide saving will bring about persistent deflation with all of its accompanying problems. The economy is trapped in a cycle in which firms cannot invest until they have repaid their asset-bubble debt, but they cannot repay their asset-bubble debt until the private sector decides to resume investment. As the Japanese experience has shown, this cycle can persist for as long as 20 years.

What are the key figures to watch?

The fundamental trigger of a Balance Sheet Recession is the rapid increase in private sector debt. Through the mechanism outlined above, this increase in debt brings about sustained and systematic private-sector savings. Consequently, the key markers of a Balance Sheet Recession can be read in asset prices and flows of funds data. If 1) the economy is relatively leveraged, 2) fixed assets are a significant component of firm value, 3) asset prices have fallen rapidly, and 4) the private sector has moved into sustained financial surplus (net savings), then a Balance Sheet Recession is likely to be taking place. Looking beyond the core mechanisms, other markers of a Balance Sheet Recession include weak consumption data, poor private investment, and poor investor sentiment concerning assets.

Is China entering into a Balance Sheet Recession?

The Chinese economy is exhibiting a number of the key indicators of a Balance Sheet Recession. However, as we will show, it is unlikely that such a recession has already arrived. Moreover, a Chinese Balance Sheet Recession is unlikely to be as severe as Japan’s financial Crisis or the Great Recession.

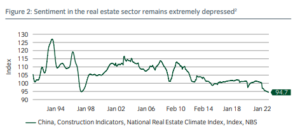

Firstly, the most likely candidate for a recession-triggering asset in China is real estate. Respectively, real estate, at its highest point in the mid-2010s, and construction accounted for 25-30% and 6.9% of GDP. Aside from the bankruptcy of Evergrande and the bond payment troubles of Country Garden, this industry has been showing several troubling signs. As Legal and General Investment Management note, property sales and starts have been consistently falling since the pandemic. Meanwhile property completions – whilst positive – are depressed below pandemic levels. At the same time, sentiment in the real estate sector is at a 24-year low – the second lowest level since records began. The picture is also poor at the level of real estate prices. Existing home prices have fallen by 6% since 2021 with prices in tier-1 cities falling by at least 15% in the same period. This structurally important component of the Chinese economy is at risk.

Source: LGIM, Insight Investment

Secondly, Chinese private sector firms have significantly decreased their investment in fixed assets. As UBP notes, “Excluding State-owned enterprises, private [Fixed Asset Investment] came in notably weaker at 0.4% YTD y/y (vs SOEs 9.4% YTD y/y). We observe a similar trend across industrial production with the private sector contracting by -0.1% y/y (vs SOEs 8.4% y/y).” At the same time, Flow of Funds data show that Chinese private sector firms began to dramatically reduce their net borrowing towards the end of 2016 – shifting towards systematic loan repayment. This combination of falling private sector net investment and rising corporate savings is highly symptomatic of balance sheet problems

Finally, though of less significance than the indicators reported above, aggregate consumer demand appears to be depressed relative to trend levels. Sales in the retail sector have fallen significantly since the beginning of China’s post-Covid opening up. Meanwhile, “on a two-year adjusted basis, which excludes base effects from the Shanghai lockdown in 2022, retail sales remained below their 10-year average of 7.6% y/y at 5.2% y/y.

Ultimately, these data show China with a poorly performing asset class that composes a significant proportion of its total economic activity, near-zero corporate investment, net corporate savings, and weakly depressed consumption. Whilst these signs are far less dramatic than we would expect in a full-fledged Balance Sheet Recession, they are in keeping with what we would see if the economy were moving in that direction. In particular, the vast discrepancy between private and state sector fixed-asset investment is a troubling indicator that present economic normality may be being sustained by artificial state investment.

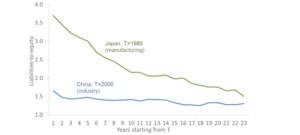

However, whilst these signs do resemble a Balance Sheet Recession, it is important to note some distinguishing features of the Chinese case. First and foremost, the Chinese financial sector is far less open than its Western competitors. Restrictions on mortgage lending and high down payment minimums on homes are common and mortgages only account for 20% of total bank loans. Moreover, Chinese corporations average just below a 1.5 Liabilities-to-equity ratio, a figure in keeping with many developed countries and far below the leverage of Japan during its asset bubble. Additionally, despite the relative importance of the real estate industry, land value accounts for only 2.4% of total assets in China. For these reasons, it is important to take the significance of these warning signs with a grain of salt.

Source: Allianz GI

Source: Allianz GI

Will China be able to cope?

The most promising aspect of China’s potential Balance Sheet Recession is the capacity of the Chinese government to respond to it. If the model is correct, then the primary cause of persistent economic stagnation is the sustained decision of the private sector to repay its loans whilst refusing to take out any new credit. In effect, profits are extracted from the circular flow of income and deposited in a banking sector where they will remain unused. Richard Koo argues that the solution to this problem is simple. If income is being extracted from industry and deposited in the financial sector, then it is the responsibility of the state to borrow unused credit from banks to reinject into industry. The government must pursue an expansionary fiscal policy. If this is done, then firms will be able to pay off their debt en masse without causing a deflationary crisis. Eventually, firms will complete their debt repayment and begin to return to positive investment. At this point, the government can cease fiscal stimulus and allow credit to be transferred from banks to firms as it would under normal economic conditions. Through government intervention, the economy can move from Type 4 back to a healthy Type 1.

As Koo points out, the Chinese government is particularly well-equipped to engage in this type of Fiscal stimulus. At the beginning of the Great Recession, the American Government pursued a fiscal stimulus of approximately $500 billion from 2009-2010. By contrast, the Chinese government issued a stimulus of $586 billion in an economy almost ⅓ of the size. As a percentage of GDP, this decision was enormous. Moreover, whilst American stimulus was significantly distributed through subsidies, bailouts, and tax rebates, Chinese stimulus largely took place directly through SOE expenditure and infrastructure construction. This latter method more directly addresses the problem of insufficient net borrowing. With the strengthening of State-owned enterprises under President Xi, this type of response is likely to be just as effective now as it was in 2008.

Conclusion

Richard Koo’s model provides a highly persuasive account of the sort of recession we can expect in a sophisticated economy suffering from the aftermath of an asset bubble. In several key statistics, we can observe many of the prerequisites for such a Balance Sheet Recession in contemporary China. In particular, high corporate savings, a weakening property market, and falling private sector Fixed Asset Investment are all early warning signs of balance sheet problems to come. However, it is important to note that the Chinese economy is far less at risk of the structural fallout of asset bubbles than many developed economies. At the same time, it is important not to overstate the role of the real estate sector in Chinese corporate financing. Finally, we can be optimistic that if a Balance Sheet Recession were to materialise in contemporary China, the default policy response is likely to be its best solution.

Harry Toube

Harry Toube is an undergraduate student of Economics at King's College London. Interests lie in Chinese development and market analytics and the political-economic relationship between representation and sovereignty.