By Caimin Corcoran, MSc Finance at Michael Smurfit Graduate Business School

Introduction

As covered in the first part of my publication, Iceland’s banking system had experienced a mini-crisis known as the ‘Geyser Crisis’ in 2006. Many of the significant faults in the banking system were exposed by a brigade of foreign analysts from Merrill Lynch and Danske Bank. Three months later, and the nation luckily emerged relatively unscathed.

What should have followed was a clear, proactive and comprehensive response from Icelandic authorities. Instead, the complacent mindset synonymous to many at the time had overruled any better judgement that might have existed.

Crisis Response

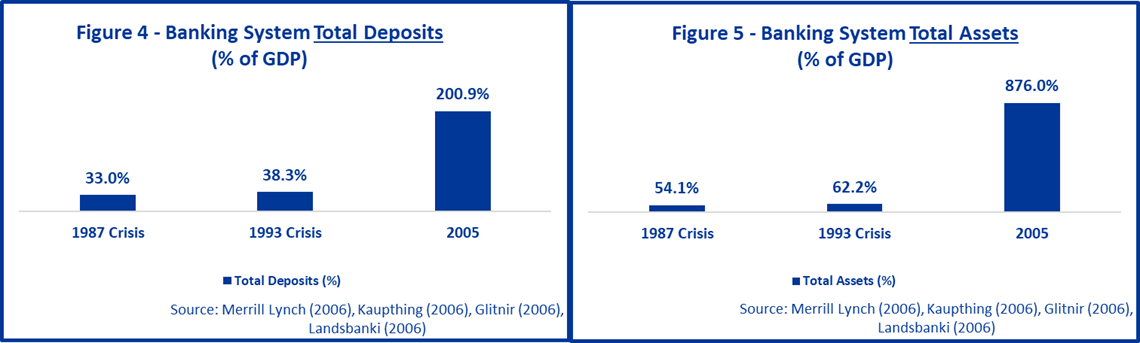

What should have accompanied the end of the ‘Geyser Crisis’ was a strong response from Icelandic authorities to eradicate the massive systemic risk that lurked over Iceland’s banks. Instead, public encouragement of the banks to grow their assets further by the government would suggest a failure to learn from mistakes. As can be seen in Figures 4 and 5 below, both the 1987 and 1993 banking crises are entirely overshadowed by the size of the banking system in 2005, highlighting the extent of the problems the nation would face in a potential banking system collapse. To make matters worse, the banking system went on to grow another 35% in 2006 and 24% in 2007.

Reserves: Saving for a Rainy Day

Since the ‘Geyser Crisis’, outside analysts have expressed their concerns about the Central Bank of Iceland’s (CBI) ability to provide liquidity or solvency to Iceland’s banks and the overall size of the banks relative to the Icelandic economy. Per the CBI’s lender of last resort function, the institution must provide reserves on demand for the banks to avoid a liquidity crisis or, worse, a solvency crisis.

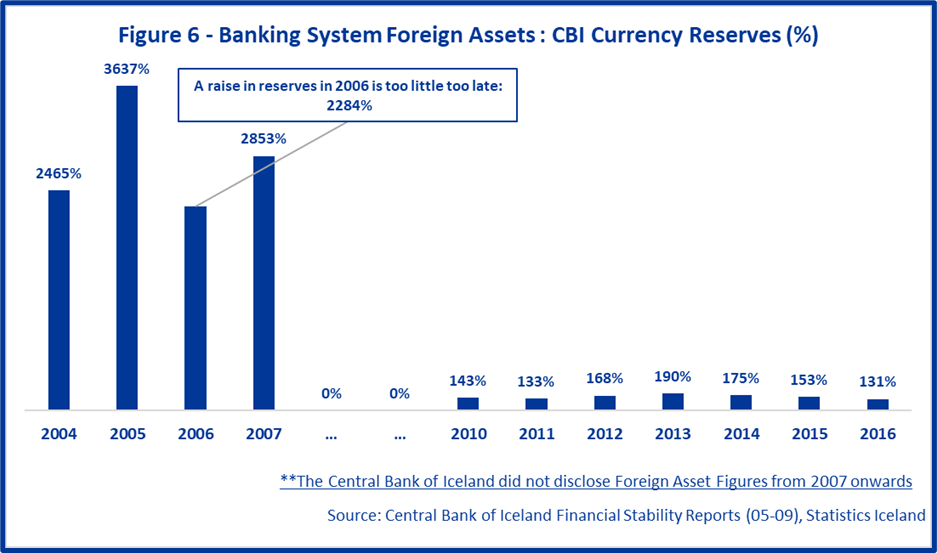

One element of particular concern was the CBI’s foreign currency reserves or lack thereof. At the Geyser Crisis, the CBI held a meagre 1 billion euro in foreign currency reserves, roughly equal to the total turnover on the ISK currency market on April 21st. The CBI did double their reserves that year, but this was far too insufficient, as illustrated in Figure 6 below.

The CBI, as illustrated above, has since taken appropriate measures to increase the proportion of foreign reserves to foreign assets in the banking system. At Lehman’s collapse, many banks could still depend on their national central bank for liquidity. The CBI’s limited foreign reserves left the GKL banks without a backstop for stability. While it is unclear the exact impact that increasing reserves could have had on mitigating the crisis, it is apparent that this more robust backstop for the banks would have provided a form of resilience to the crisis, which was limited in 2008.

Aligning Fiscal Policy with Monetary Aims

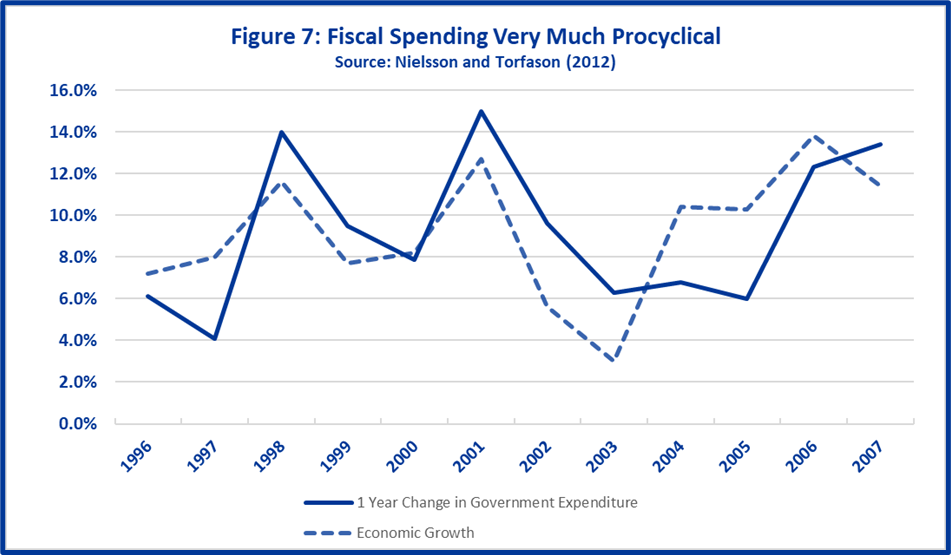

As illustrated in Figure 7 below, the Icelandic government contributed massively to the economy overheating in their entirely cyclical approach to fiscal spending. Strong spending in capital projects was one of the main contributors to the solid economic growth that brought Iceland to this point. Iceland has suffered from a misalignment of the national governments and Central Bank’s goals. Without cooperation from the Icelandic government, the CBI’s intended effect of monetary policy tools was severely hampered. The policies of the Icelandic government during a time of robust economic growth have been nothing short of unnecessarily aggressive and reckless. The Icelandic government slashed corporate taxes in half to 18% in 2002 and down to 15% in 2008. Income tax was reduced in each year from 2006 to 2008. Thus to end the overheating of the economy and banking system, the government should have 1) increased tax rates and 2) cut the pro-cyclical government capital expenditure.

Interest Rates as a Monetary Policy tool

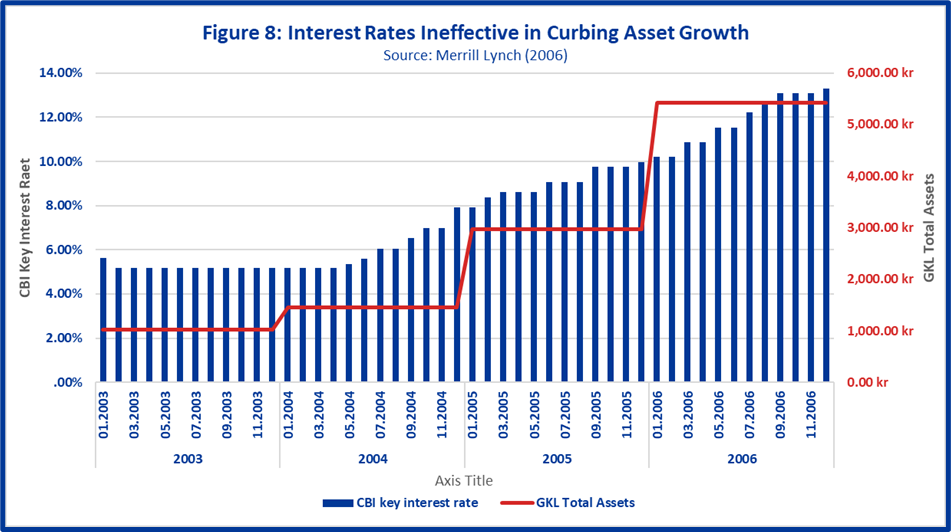

Raising rates as a policy tool was arguably the least effective in the CBI’s arsenal at the time – but a tool nonetheless. Increasing interest rates has long been argued to be ineffective for curbing growth when asset bubbles exist – which was the case in Iceland. Even less appealing to Iceland was that higher rates also bring unwanted deposits from foreign investors seeking to benefit from the carry trade. The carry trade is notorious for placing unwanted volatility on the domestic currency of choice, in this case, the Krona, with the higher demand for the currency causing its price to fluctuate.

Interest rate hikes were ineffective on their own in fighting bank asset growth. However, the combination of several contractionary measures and the rising interests could have had a more pronounced effect on the banking system. These measures together could and should have curbed the vast growth of the nations banks.

Supervision

After the irreparable damages that had been done to the reputations of Glitnir, Landsbanki and Kaupthing (GLK) in 2006, it was imperative to improve supervision of the banks to avoid another crisis. To be effective, supervision must be intrusive, adaptive, proactive, and comprehensive. During the Geyser Crisis, outsiders noted the prevalence of owner lending by the banks; the largest groups of borrowers in all three banks were indeed the bank’s owners. Comprehensive supervision could have flagged this issue before another crisis unfolded, and the issues of connected lending[1] and ill-intentioned loans would have been resolved somehow. Instead, supervision remained an extremely complacent[2] activity that drew criticism in the 2008 post-mortem. When the Icelandic banking system collapsed, the extent of the crisis was unknown due to the lack of supervision. Connected lending between owners of banks and their extended families had made it extremely difficult to gauge the quality and quantity of the loans; the recovery rates on these loans turned out to be 4%-6%.

A more potent, more intrusive supervision would have given Iceland a more precise picture of the urgency of the pending collapse. The authorities would then have acted more promptly and accurately, given the newly-improved access to information about each bank’s loan book.

Conclusion

As outlined by the Special Investigation Commission, a timely response from Icelandic authorities after the Geyser Crisis could have prevented the collapse of the banking system, and subsequently, the collapse of an entire nation. Failure to acknowledge the ‘canary in the coal mine’ was typical of the complacent attitudes shown by the financial supervisors and the government. Icelandic authorities refused to acknowledge the repeated signs of overheating, and in some cases, public concern from various foreign entities, namely The Bank of England and various credit rating agencies. While the banking system bears most of the blame for the collapse, inactivity from the regulatory authorities such as the FSA and the CBI makes more than the banks responsible for the crisis.

Adhering to any of the above-proposed policies would have yielded limited, if not negligible, results. The conjunction of these policies in tandem should have halted one of the most bloated, overheated banking systems globally.

[1] Connected Lending Connected lending is a situation in which the bank’s controlling owner extends loans of inferior quality at lower interest rates to himself or his connected parties, in this case, the other Icelandic financial institutions.

[2] To illustrate, the CBI considered the financial system to be broadly sound in 2007, the Icelandic FSA also deemed the banks to be as strong, if not stronger, than their European counterparts.

Contributor to The London Financial

We combine research produced by students and early professionals into a single website, breaking down the barriers to entry individuals face in a number of industries.

Contributor opinions are their own and do not necessarily reflect the stance of the LF.