By Kings Equity Research Group

INTRODUCTION

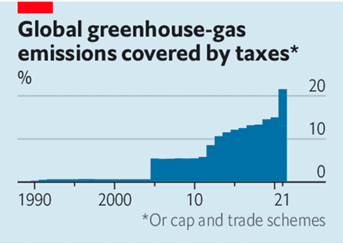

With the concept of sustainability becoming increasingly relevant, emissions trading schemes (ETSs) have become increasingly popular for setting a legal limit on global carbon emissions by issuing finite licenses that are then exchangeable between polluting firms on a secondary market. Deviating from the adversarial nature of taxation, these cap and trade policies are often heralded for theoretically enabling market forces to incentivise clean and sustainable production, with policymakers often tightening the emissions cap from year to year.

With that in mind, theory does not always translate to practical results, with problems such as lack of enforcement and over-lenient emissions caps often highlighting the prominent flaws of the ever-popular cap and trade scheme.

In saying that, this article will look to dissect two of the world’s most well-known yet contrasting ETSs; the longstanding EU ETS launched in 2005; and the new yet rapidly booming Chinese ETS, which began operation in July 2021 and looks to have already overtaken the EU ETS as the world’s largest ETS. By sifting through both the initial struggles as well as the recent successes of the EU ETS, it is hoped that one can truly perceive how a ‘learning-by-doing’ mentality may not only assist China in succeeding with their ETS but may enable unprecedented and effective reductions in carbon emissions to be enjoyed globally in the coming years.

CASE STUDY: EU’S ETS

The ETS is a subsidy scheme for polluters… companies have consistently received generous allocations of permits to pollute – Corporate Europe Observatory

Arguably the EU ETS has the highest global profile, first initiated in 2005 with a long-term goal of attaining a climate-neutral Europe by 2050; covering over 11,000 installations across the EU. Having reduced carbon emissions by 35% between 2005 and 2019 and with a set target of 55% by 2030. The EU has long heralded it as an innovative tool for cost-effectively reducing greenhouse gas emissions. But, it is of course debatable how much of these carbon reductions are attributable to the ETS.

With that said, the scheme has not been devoid of criticism throughout the distinctive trading phases it has transitioned through. The ‘learning by doing’ phase of 2005-2007 saw the participation of power stations that contributed 40% of EU emissions, yet a questionable cap that was actually higher than the 2005 status quo emission level provided scope for governments to increase emissions, resulting in extreme permit price volatility and a net emissions increase of 1.9%.

Fittingly, the second trading phase of 2008-2012 saw rectification in terms of a tighter emissions cap (2% lower than 2005), leading to increased carbon prices as additional sectors such as aviation were introduced within the scheme. Nonetheless, permits remained oversupplied and under-priced, with the ensuing Global Financial Crisis only serving to further disincentive installations to reduce carbon emissions.

In more positive news, the most recent phase (2013-2020) saw encouraging signs in the form of carbon capture and storage systems being installed, and continued efforts to tighten the overall EU cap through specific allowances allocated to individual EU states. Further changes included incorporating more gases like nitrous oxide and perfluorocarbons, as well as a gradual shift from freely allocating permits to auctioning them off instead; proceeds can be used to fund further green innovation.

With that said, heading into phase four (2021-2030), concerns around permit allocation and price volatility will likely persist, as the freely-allocating price mechanism will often fail to deter firms from cutting carbon emissions when faced with exogenous demand and supply shocks that may strike an economy at any time. While in recent years permit prices have gradually begun to rise again amidst the continuous tightening of the emissions cap, EU policymakers must remain aware and vigilant of the dangers of permit price crashes, and thus a myriad of proactive and stabilising measures have been discussed and implemented heading into phase four (2021-2030) of the scheme.

One such measure is the market stability reserve (MSR), a mechanism introduced in 2019 that enables policymakers to rectify supply-demand imbalances in the carbon permits market by taking excess allowances out of circulation, akin to how certain central banks often look to their official reserves in monitoring a managed or pegged exchange rate. Possessing a twofold effect, a measure like the MSR not only acts as an automatic stabiliser for the EU carbon market in the face of future exogenous shocks, but more significantly enables for discretionary adjustments of the supply of carbon permits on the market, subsequently softening the impact of permit price volatility and overallocation. Appropriately, other measures like the postponement of further permit auctioning have also been explored in ensuring stability in the EU carbon market, and it appears inevitable that further innovative reform must emerge in the coming years as the EU continues on its now legally obligated battle towards climate neutrality by 2050.

All things considered, even with its ongoing battles with incentive issues and supply-demand inefficiencies, the EU ETS remains a conceptually sound policy that has the utmost potential to sever carbon emissions significantly both across Europe and on a global stage, so long as the two key ingredients of transparency and innovation are well respected for a long time to come.

CASE STUDY: CHINA’S ETS

China is the world’s largest greenhouse gases emitter, exceeding the world’s second-largest emitter, the US, by approximately 50% (CNBC). However, this status-quo may not remain for long. In 2011, China announced the establishment of seven ETS pilots; covering the five cities of Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Chongqing; and the two provinces of Guangdong and Hubei. In 2016, an eighth provincial pilot was launched in Fujian. Each pilot was made unique to ascertain the best method for national implementation. Perhaps coincidently, the piloting scheme’s transition to nationwide implementation in June 2021 closely followed Xi Jinping’s ‘double carbon pledge’ at the UN in September 2020; pledging China would achieve its carbon peak by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. Although the nationwide ETS was only implemented a few weeks ago, China’s ETS already covers more greenhouse emissions than produced in the entire EU. Despite this feat, China’s ETS is far from ascertaining its true potential in delivering a greener society. What issues then preside in China’s ETS, and how could they be solved?

Criticism #1: Scope

“The power sector is too lonely“ – Prof Duan Maosheng of Tsinghua University

Similar to its piloting scheme, China’s nationwide ETS will be restricted in scope. During commencement, only the power sector will be subject to the ETS. Despite this limitation, it will overtake the EU’s ETS and become the world’s largest ETS. According to the Rhodium Group, the EU was responsible for 6.4% of global greenhouse emissions in 2019. Contrast this figure to China’s power sector, responsible for 40% of China’s emissions, translating to 15% of global CO2 emissions (CarbonBrief). Regardless of these statistics, initial focus on the power sector will make it easier to find solutions towards monitoring and compliance; two significant obstacles shared by ETSs globally. According to Sino-Carbon’s Chen, starting with the power sector was significantly influenced by its concentrated state-owned status. In China, the power sector is dominated by state-owned enterprises, where they oversaw 48% of nationwide power capacity in 2019 (CarbonBrief). Therefore, by having the state scrutinise state-run entities, it becomes easier to navigate and find solutions regarding monitoring and compliance which can thereafter be applied in the future.

Criticism #2: Price

The current market lacks liquidity and carbon prices are low; making it challenging to form practical constraints on producing greenhouse gases – CITIC Securities.

The price of China’s carbon permits is also uncertain. The China Carbon Forum predict prices to start at ¥49 ($7.56)/ton. This estimation would be twice the average of Chinese ETS pilots; within a similar range of the US ETSs; yet far lower than the €50 ($58.91) trading levels experienced under the EU ETS. Arguably, China’s low prices minimise the incentives for companies to pollute less and develop greener technologies. But what then would be a reasonable price? Economists Joseph Stiglitz and Nicholas Stern created a commission on the carbon price in 2017 and concluded that if prices were to impact behaviour, carbon should be priced between $40 and $80 by 2020; and increasing to between $50 and $100 by 2030. Unfortunately, predictions do not seem optimistic; for example, Citi expects China’s ETS prices to only rise to $25/ton by 2030.

Criticism #3: Absence of a Cap

“Improvements must be made as soon as possible: introduce an ‘absolute cap’ to ensure the scarcity of the resources and stabilise the carbon price.” – Prof Duan Maosheng of Tsinghua University

Unlike the EU, China’s ETS does not operate a cap and trade scheme where the carbon allowance supply gradually reduces to ensure emission reductions. Instead, China operates a ‘flexible cap’ whereby intensity affects the allowance supply. This ‘flexible cap’ utilises an intensity formula that considers total power generation, power generator’s size, and fuel type, among others, to calculate carbon allowances. Aside from reducing emissions, cap and trade schemes better control supply and establish greater market predictability, crucial if the ETS ecosystem is advanced – as advocated by the former governor of the People’s Bank of China, Zhou Xiaochuan.

Summary

It is understandable that China, the largest country to implement a national ETS, currently has an imperfect ETS. We should not criticise upon these imperfections but rather criticise inaction for fixing these imperfections. China appears to hold a proactive attitude, suggesting it will genuinely alleviate issues associated with its ETS. Xi Jinping seems authentic in his double carbon pledge of 2020. It followed the nationwide ETS launch in 2021 and the announcement of the 14th Five Year Plan for 2021-2025 with no GDP target (an unprecedented move) instead of focusing on sustainability. All these events signify that China is transitioning from quantity to quality growth, and ETSs will play a fundamental role in this transition.

CONCLUSION

Ironically, industrialists, amongst others, portray implementing environmentally-friendly measures as being ‘anti-capitalist’. In reality, the production of greenhouse gases and all other forms of ESG should have always been addressed in an efficient and proper market economy. ETSs provide a means of addressing negative externalities, shifting aggregate demand to reach ‘proper’ equilibrium. However, ETS schemes are currently far from perfect and capable of delivering such potential. As seen from the historically disappointing outcome of price instability in the EU carbon market and over-prudence in the setting of an initial EU emissions cap, it is clear that specific levers must be actively maintained to produce a successful cap and trade scheme. Alongside these reforms, central authorities could consider making ETSs more liquid by allowing institutional investors to take part and introducing derivatives. But is greater liquidity for ETSs good? Perhaps a topic for another article. Overall, given that innovative reform and new legislation is constantly under the global microscope with carbon neutrality targets of 2050 and 2060 set by the EU and China, respectively, ETSs appear to be a pivotal fertiliser in the global transition towards efficient, long-term focused, capitalist markets. Behold the age of green capitalism.

Contributor to The London Financial

We combine research produced by students and early professionals into a single website, breaking down the barriers to entry individuals face in a number of industries.

Contributor opinions are their own and do not necessarily reflect the stance of the LF.