By Caimin Corcoran, MSc Finance at Michael Smurfit Graduate Business School

- Published as part of our ‘Deep Dive’ Section, promoting in-depth pieces which analyse underrepresented issues and challenge conventional narratives.

Introduction

I know what you are thinking: Iceland is just a country of beautiful natural landscapes with glaciers and black sand beaches. Precisely what I would’ve thought until I peeled back the surface and unearthed a banking system of unfettered greed, industry-wide denial and an air of corporate indestructibility.

This brief paper on the Icelandic banking system has two parts. Part One will outline the prominent fault lines and self-destructive ideas in the Icelandic banking system. Part Two will outline the missed opportunities which could almost certainly have avoided a banking catastrophe.

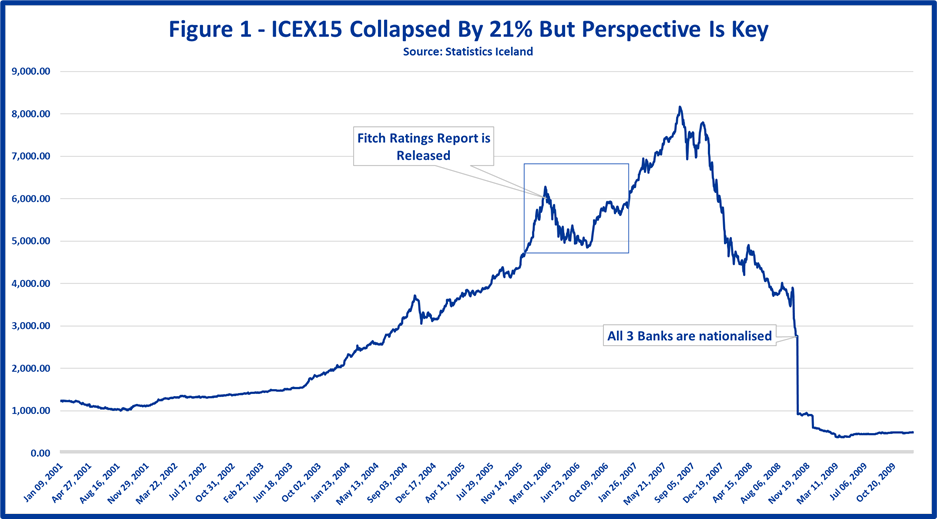

The extent of the damage caused by the Icelandic banking crisis during the Global Financial Crisis is well acknowledged. Three of the country’s largest banks, accounting for 80% of Iceland’s banking system, had to be nationalised in the space of 3 days. Economic conditions had deteriorated so severely in 2009 that local media outlets in Iceland were told by the Public Health Institute to write more positive stories.

Prior to the collapse, the growth experienced by Icelandic banks was even greater than that experienced by Irish banks. A critical mistake of many governments before and during the global financial crisis was their inability to respond to warning signs in an effective and timely manner. Iceland was no exception. Having endured a mini-crisis in 2006, Iceland could have learned lessons, but they did not. In this article, I have attempted to illustrate Iceland’s failings in what was, for the most part, an avoidable meltdown.

Canary in the Coalmine: The Leadup to the ‘Geyser Crisis’

Iceland’s banking system first displayed signs of faltering in the so-called Geyser Crisis of Spring 2006. ‘Geyser Crisis’, as coined by Danske Bank, represented the geyser-like turbulence to come for the Icelandic banks and the Icelandic economy. At the turn of the millennium, bank asset growth had exploded due to the privatisation of some major banks and consolidation in the industry. The three largest banks in Iceland: Glitnir, Kaupthing and Landsbanki (GKL), had an average annual growth in total assets of 90% from 2000 all the way up to 2007. By this time, GKL now accounted for 80% of the nation’s financial system, and their assets stood at ten times Iceland’s GDP; Ireland’s banking system, by contrast, stood at approximately 5x GDP. Rating agencies, investment banks, and government officials should have been alerted to the signs of overreliance on the national banks for economic growth. In actuality, this was not the case.

Meltdown Iceland

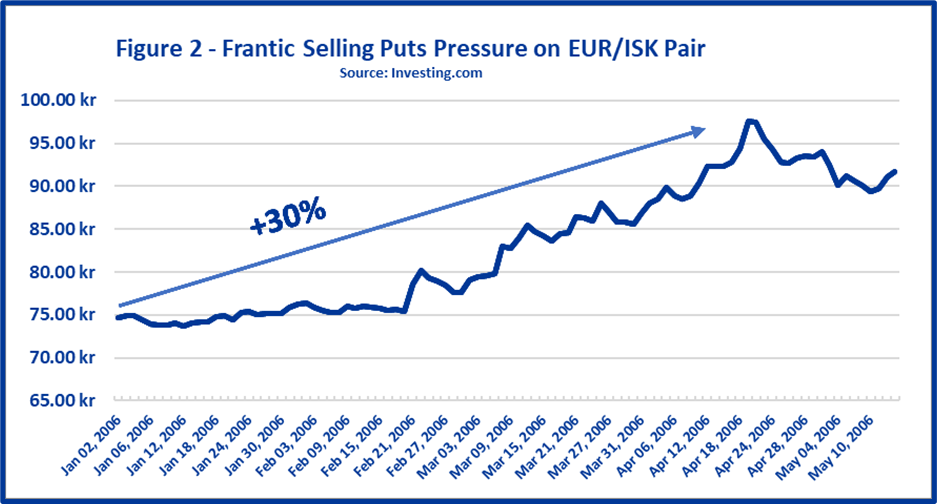

On the 21st of February 2006, Fitch Ratings Agency revised its outlook for Iceland from “Stable” to “Negative”, which had highlighted the frailties in the nation’s economy at the time: unabated credit growth of 30% per annum, an unsustainable current account deficit and external debt reaching levels of almost 300% of GDP. Heavy coverage followed from institutions worldwide[1], which caused frantic panic selling of the Icelandic equity market, currency market (Figures 1 & 2) and fixed income markets. JP Morgan cited in their report that this attention drew focus on the structural issues of the Icelandic banks. It was here where the ‘Geyser Crisis’ would begin. The negative attention brought to Iceland’s financial system would cut off Iceland’s funding from medium-term notes in Europe, creating major short-term funding headaches for the banks. The nation was in turmoil; inflation had spiked to 8% by April 2006, the ICEX15 index and the Krona endured several sell-offs in the months of Spring, and the Icelandic Krona (ISK) trading volumes had seen levels close to 7% of GDP.

The Geyser Crisis comes to an end

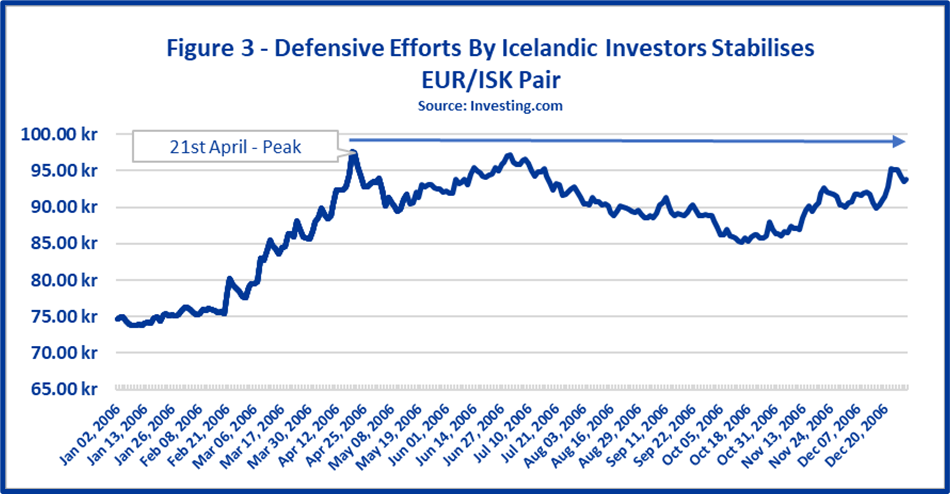

The Geyser crisis came to a halt in May 2006, 3 months after the report from Fitch Ratings had been released. Media outlets and investors alike had suffered what was referred to as ‘Icelandic Fatigue’ and turned their attentions elsewhere. Iceland’s economy emerged from the crisis unscathed (relative to 2008), yet no preventative policies or measures of note were implemented after that, allowing Iceland’s banking sector problems to escalate.

On the 20th of April, companies in the private sector, fishing firms, and pension funds pooled together their resources to coordinate a defence of the ISK. The following day (as highlighted in Figure 3 below) marked a shift in momentum for the ISK. Each sale of the Krona was matched by these private investors, and one by one, hedge funds began to take profits and leave the country due to the strong resistance from these private investors. This steadied the currency crisis in the country, which had seen the ISK shed value consistently for the first four months of 2006.

A resoundingly positive report from Frederic Mishkin, a former member of the Federal Reserve board of governors, also contributed to restoring faith in the nation and the banking system. An excerpt of the report includes: “its (Iceland’s) financial regulation and supervision is considered to be of high quality”. This would later turn out to be one of the most controversial documents surrounding the global financial crisis due to the false claims and inaccurate statements made throughout the document; however, the validation in the report was enough to restore the confidence of institutions and investors. Mishkin was incidentally paid compensation of approximately $124,000 for the report, which was not disclosed at the time.

Conclusion

Despite all of the warning signs that the Icelanders had encountered, little was done to bring control to the financial system. Iceland had many opportunities to curb the massive, unsustainable growth in banking in the years prior to 2006. Neither the Central Bank of Iceland nor the financial regulator (FSA) stepped in to take preventative measures – ultimately leading to a cataclysmic meltdown of the Icelandic banking system.

[1] Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, Danske Bank, JP Morgan and RBS targeted Icelandic banks, Icelandic Krona, Debt and Credit Default Swaps in their research reports.

Contributor to The London Financial

We combine research produced by students and early professionals into a single website, breaking down the barriers to entry individuals face in a number of industries.

Contributor opinions are their own and do not necessarily reflect the stance of the LF.