By Laura Maxwell, Contributor and undergraduate at King’s College London

Kanye West fell from public favour in the late 2000’s following a series of public outbursts, including declaring live during a Concert for Hurricane Relief benefit that George Bush, the sitting President of the United States at the time, “doesn’t care about black people.” This famously culminated in 2009 when West interrupted Taylor Swift’s acceptance speech for Best Female Video at the MTV Video Music Awards, proclaiming “…Beyoncé had one of the best videos of all time,” referring to the latter’s internet viral smash hit Single Ladies. Whether you agree with West’s musical preference or not, it was certainly the most dramatic event of the evening, neatly positioning him as music’s new favourite villain. That’s no exaggeration either. Even America’s newly elected President, Barack Obama, weighed in on the debacle, referring to West as a “jackass.” Following the awards ceremony, it is reported that West was even advised by those closest to him to leave the United States, seeking refuge from the American public and media as far away as Japan and Rome. When he did finally return to the US, it was, ironically, in the President’s home state of Hawaii.

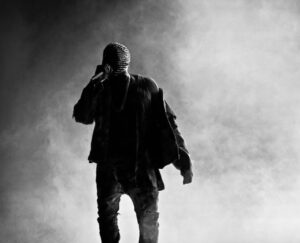

It was here that West wrote and recorded the majority of what would become My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. Considered by many to be West’s magnum opus, the record was released to critical acclaim, entailing both artistic and musical experimentation featuring collaborative projects by an extremely versatile roster, ranging from JAY-Z to Bon Iver and Chris Rock. Taking inspiration from his self-exile, the record indulges and pays homage to Italian Renaissance art and music. Once more, according to one producer of the record, West took particular care in the project’s lyricism, it being the first time he had taken the time to write his lyrics down as opposed to his regular improvisation once in the recording booth. Its musical grit and excellence aside, the record is of high importance as it was not only Kanye’s chance to redeem himself as a credible hip-hop artist, but also personally in the public eye. Many searched the record for a typical Kanye West antic or hidden snubs at Taylor Swift and/or his own music industry. Instead, they found an intimate exploration of West’s deepest, darkest thoughts, touching on subjects such as love, desire, infidelity and madness; my Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy remains a hip-hop staple over a decade since its release.

In the same year Kanye West disgraced himself at the MTV Video Music Awards, America witnessed the election of its first black President, and the weight of this position did not fall on deaf ears, certainly not those of Barack Obama himself. Indeed, Obama took much care in crafting an image of himself as, of course, an African American, but with appeal to the white imagination. Birthed and raised by a white mother, Obama showed universal resonance, stressing his multifaceted heritage. Obama made a point of demonstrating his connection to the white electorate, noting in a sit-down interview with Oprah Winfrey in 2006 that he has “relatives that look like Margaret Thatcher.” In many ways, Obama, a Harvard-educated, Christian man with southern roots, represented the ‘acceptable’ African American; suppressing his more recognisable black culture; becoming easily palatable to white audiences. It was inevitable during this time that a juxtaposition between the new President and Kanye West would emerge; comparing their personal conduct and supposed ‘values’ that, on a surface level, appeared to be at opposite ends of the black spectrum. Alone, West seemed arrogant, but compared to his neat, composed and modest political counterpart, the case could be made for his insanity.

What does this say about the blackness that America is willing to accept and, once more, propel to positions of power? Do black Americans have to conform to white ideals in order to gain respect from their white counterparts? This expectation can be traced outside of Kanye West and the hip-hop community.

The American press has historically demonised people of colour who display less than desirable behaviours, feeding into a wider conversation surrounding how we respond to and talk about mental health generally, but also specifically in the black community. Once more, the mental instability of black celebrities is often belittled and even made into a point of humour, by the white and black communities alike. Consider this against the forgiveness we afford to white celebrities, or the way in which we are able to view white mental instability through a more sympathetic lens, even going as far as glamorising it retrospectively in artistic mediums. This can be observed in homages the music industry and society continues to pay to the likes of Kurt Cobain and Mac Miller; both of whom were avid recreational drug users with a plethora of mental illnesses, yet we tend to remember them through fond memories or the art they produced. The level of respectability we expect from black people generally but black men in particular reflects a double standard that is deeply rooted in racist suppositions inflicted upon black people in western societies.

Kanye West is a caricature for the ultimate white fear; aggressive, arrogant and uncontrollable blackness. The MTV Music Awards posited the perfect stereotypes of black men, juxtaposed against the ‘innocent’ and ‘vulnerable’ white woman. These tropes have existed for hundreds of years. Most famously, D. W. Griffith’s 1915 The Birth of a Nation presents African Americans as lazy, incompetent, dishonest and dangerous. Arguably its most famous scene depicts its black character (white actor Walter Long performs in black face), Gus the Renegade, attempting to marry and rape Mae Marsh’s Flora Cameron, resulting in Cameron leaping to her death from a precipice rather than be intimate with a black man.

The hyper sexualisation and criminalisation of black people has been present within film and media for decades, and this translates into wider societal narratives about black people in America and across the world that even Barack Obama was subjected to. The emergence of the infamous birther movement which claimed that Obama was not born in the US and therefore could not become President, demonstrates that even black members of high society are victim to the same ridicule and stereotyping that has plagued the black community for centuries. Those who argue that media portrayals of people of colour are trivial in the grand scheme of equality do not acknowledge the importance of representation in media, especially those representing minority communities where it is sparse and often sloppy.

We love black people for what they can do for us, not for who they are, and this speaks to a wider discourse concerning mental health. Recent conversations surrounding Kanye West’s mental stability, although potentially valid, demonstrate our inability to fully acknowledge the unspoken limitations we have constructed for respectable black behaviour and how far we have to go in addressing the intersectional facets of mental health in communities of colour. We are yet to fully accept blackness in its entirety; encompassing complex, messy and less favourable facets. This is particularly pressing for black men, who are already burdened with aforementioned stereotypes of criminality. There is little room for lapses in judgement or, lord forbid a black man, such as Kanye West, makes a mistake.

This is not to say white celebrities do not suffer at the hands of either mental illness or the press. One can’t help but think about the likes of Britney Spears, Lindsey Lohan and Amy Winehouse and how they have been and continue to be unfairly targeted by the media. But what is clear is there are systemic and routine limitations on the treatment of people of colour and mental health, which is largely informed by mutually reinforcing socio-economic conditions, producing entrenched inter-generational, racial trauma. This ill treatment is reflected across various systems of oppression that operate within western society, resulting in a disproportionate presence of people of colour in American prisons and the Welfare State. Too often we are quick to judge or make assumptions about black culture and criminality yet spend little time considering why this condition exists in the first place.

Today, over a decade later, Kanye West occupies a similar space in conversation concerning his ‘wild’ antics and wider frameworks of mental health, illuminating the limited progress we have made since 2009 and how much further we need to go.